Imagine a towering tree, its branches reaching for the sky, its roots delving deep into the earth. This magnificent organism is constantly engaged in a silent, invisible process that is fundamental to its survival and, indeed, to life on Earth. This process is called transpiration, often described as the plant’s very own water cycle. Far from being a simple loss of water, transpiration is a sophisticated and vital mechanism that drives water and nutrients through the plant, cools its tissues, and even influences global weather patterns.

What is Transpiration? The Plant’s Water Cycle

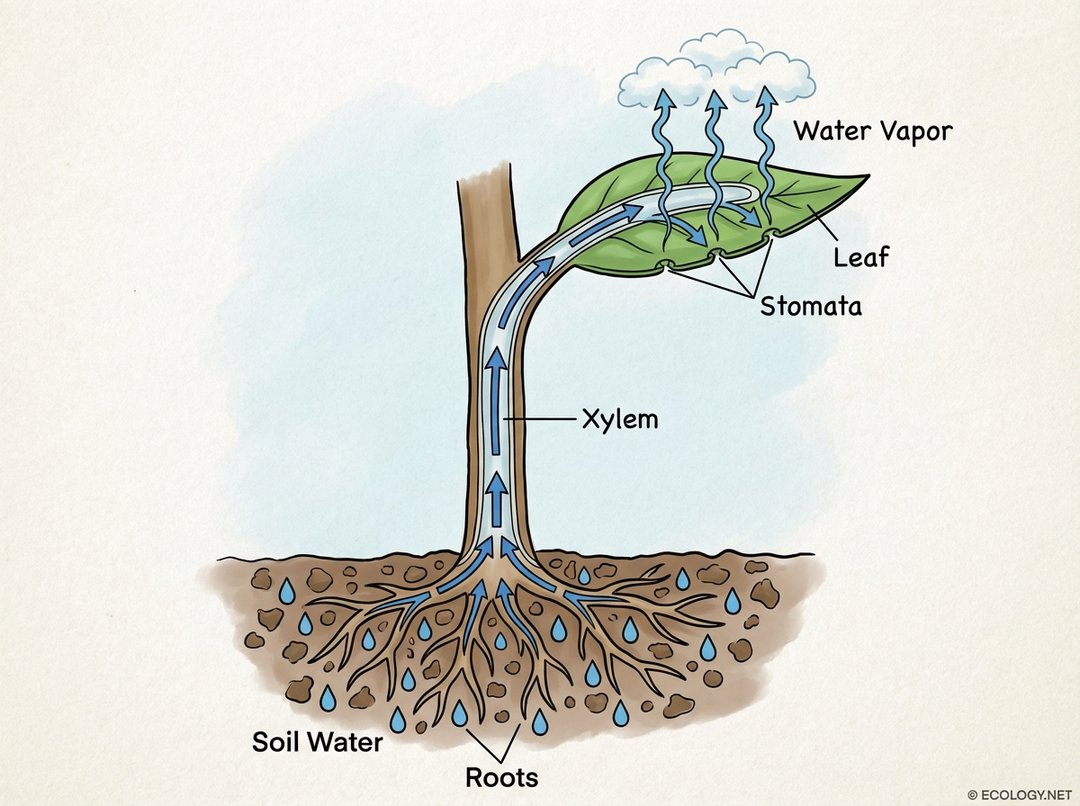

At its core, transpiration is the process by which water vapor is released from plants, primarily through their leaves, into the atmosphere. It is essentially the evaporation of water from plant leaves, stems, and flowers. While it might seem like a wasteful process, given that only a small fraction of the water absorbed by a plant is used for growth and photosynthesis, this continuous movement of water is crucial for the plant’s health and the broader ecosystem.

Think of it as a plant’s plumbing system in action. Water is drawn up from the soil, travels through the plant’s internal structures, and then escapes as vapor. This creates a continuous “transpiration stream” or “transpirational pull” that is surprisingly powerful, capable of lifting water hundreds of feet against gravity in the tallest trees.

How Does Transpiration Work? The Step-by-Step Process

The journey of water through a plant is a marvel of natural engineering. It can be broken down into three main stages:

- Water Absorption by Roots: The process begins in the soil, where roots absorb water and dissolved minerals. Root hairs, tiny extensions of root cells, greatly increase the surface area for absorption, drawing water in through osmosis.

- Movement Through the Xylem: Once inside the root, water enters the xylem, a specialized vascular tissue that forms a continuous pipeline extending from the roots, through the stem, and into the leaves. The cohesive forces between water molecules (they stick to each other) and adhesive forces (they stick to the xylem walls) allow water to form an unbroken column.

- Evaporation from Leaves: The primary driving force for this upward movement is the evaporation of water from the leaves. As water vapor escapes from the leaf surface, it creates a negative pressure or “pull” at the top of the water column in the xylem. This pull extends all the way down to the roots, drawing more water up to replace what has been lost. This is often referred to as the “cohesion-tension theory” of water transport.

The Role of Stomata: Tiny Gatekeepers of Water

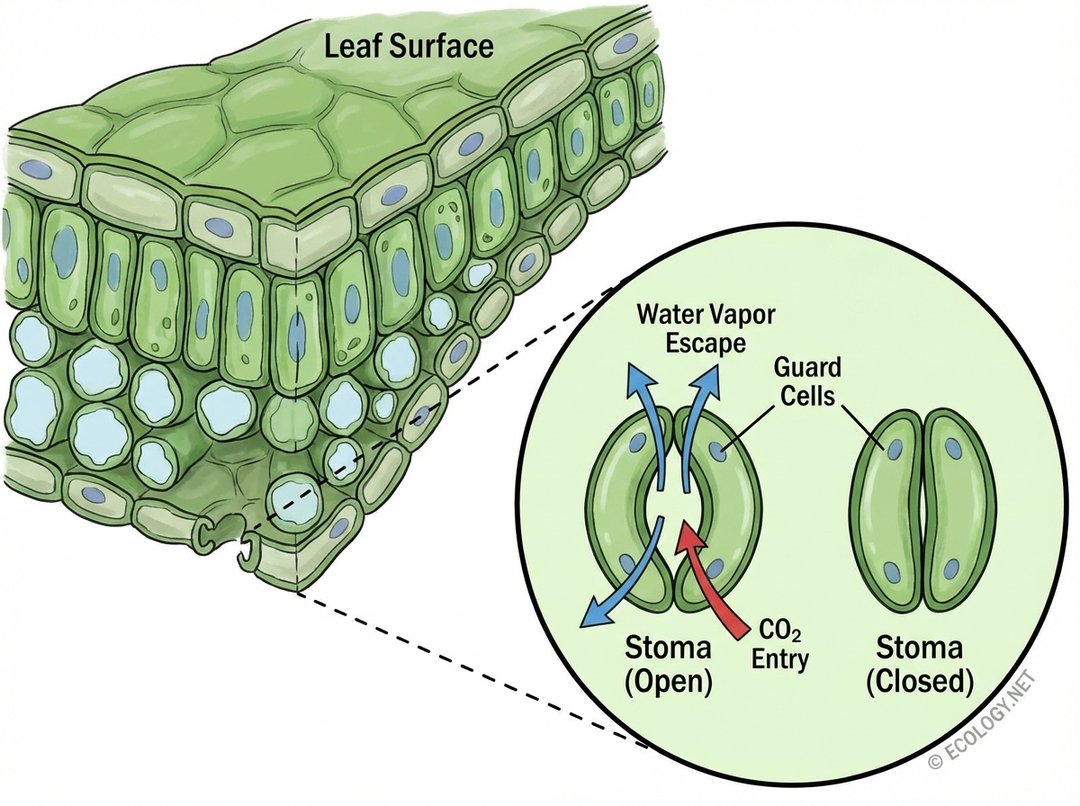

The vast majority of water vapor escapes from the leaves through tiny pores called stomata (singular: stoma). These microscopic openings are primarily found on the underside of leaves and are flanked by two specialized cells known as guard cells.

Guard cells are the true gatekeepers. They regulate the opening and closing of the stomata, thereby controlling the rate of transpiration and gas exchange. When guard cells take in water, they become turgid and bow outwards, opening the stoma. When they lose water, they become flaccid and close, shutting the stoma.

This regulation is a delicate balancing act. Plants need to open their stomata to allow carbon dioxide (CO2) to enter for photosynthesis, but opening them also means losing water vapor. Therefore, plants must constantly weigh the need for CO2 against the risk of dehydration. For instance, stomata typically open during the day when sunlight is available for photosynthesis and close at night to conserve water.

Factors Affecting Transpiration

The rate at which a plant transpires is not constant. It is influenced by a complex interplay of environmental conditions and the plant’s own characteristics:

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase the kinetic energy of water molecules, leading to faster evaporation and thus a higher rate of transpiration.

- Humidity: The amount of water vapor already in the air (humidity) affects the concentration gradient between the leaf and the atmosphere. Low humidity means a steeper gradient, accelerating water loss from the leaf. High humidity slows it down.

- Wind: Wind blows away the humid air immediately surrounding the leaf, maintaining a steep concentration gradient and increasing the rate of transpiration.

- Light Intensity: Light is the primary trigger for stomatal opening in most plants, as it signals the availability of energy for photosynthesis. More light generally means more open stomata and higher transpiration.

- Soil Water Availability: If the soil is dry, roots cannot absorb enough water to replace what is lost through transpiration. This can lead to stomata closing to conserve water, and if severe, to wilting.

- Plant Characteristics:

- Leaf Size and Number: More leaves or larger leaves mean more surface area for stomata and thus more potential for transpiration.

- Cuticle Thickness: The waxy cuticle on the leaf surface acts as a barrier to water loss. Thicker cuticles reduce transpiration.

- Stomata Density: The number of stomata per unit area of leaf surface directly impacts the potential for water loss.

- Leaf Hairs (Trichomes): Some plants have hairs that trap a layer of humid air near the leaf surface, reducing the concentration gradient and slowing transpiration.

Why is Transpiration Important? More Than Just Water Loss

While it involves significant water loss, transpiration is far from a detrimental process. It serves several critical functions for the plant and the wider environment:

- Nutrient Transport: The transpiration stream is the primary mechanism for transporting water and dissolved mineral nutrients from the roots to all parts of the plant, including the leaves where they are used for growth and metabolic processes.

- Cooling the Plant: Just like sweating in animals, the evaporation of water from the leaf surface has a cooling effect. This is particularly important for plants in hot environments, preventing overheating and damage to enzymes involved in photosynthesis.

- Maintaining Turgor Pressure: Transpiration helps maintain turgor pressure within plant cells. Turgor pressure is the internal water pressure that keeps plant cells firm and rigid, providing structural support to leaves and stems. Without it, plants wilt.

- Driving the Water Cycle: On a larger scale, transpiration contributes significantly to the global water cycle. Forests, especially rainforests, release vast amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere, influencing regional rainfall patterns and climate.

Adaptations to Extremes: Xerophytes and Hydrophytes

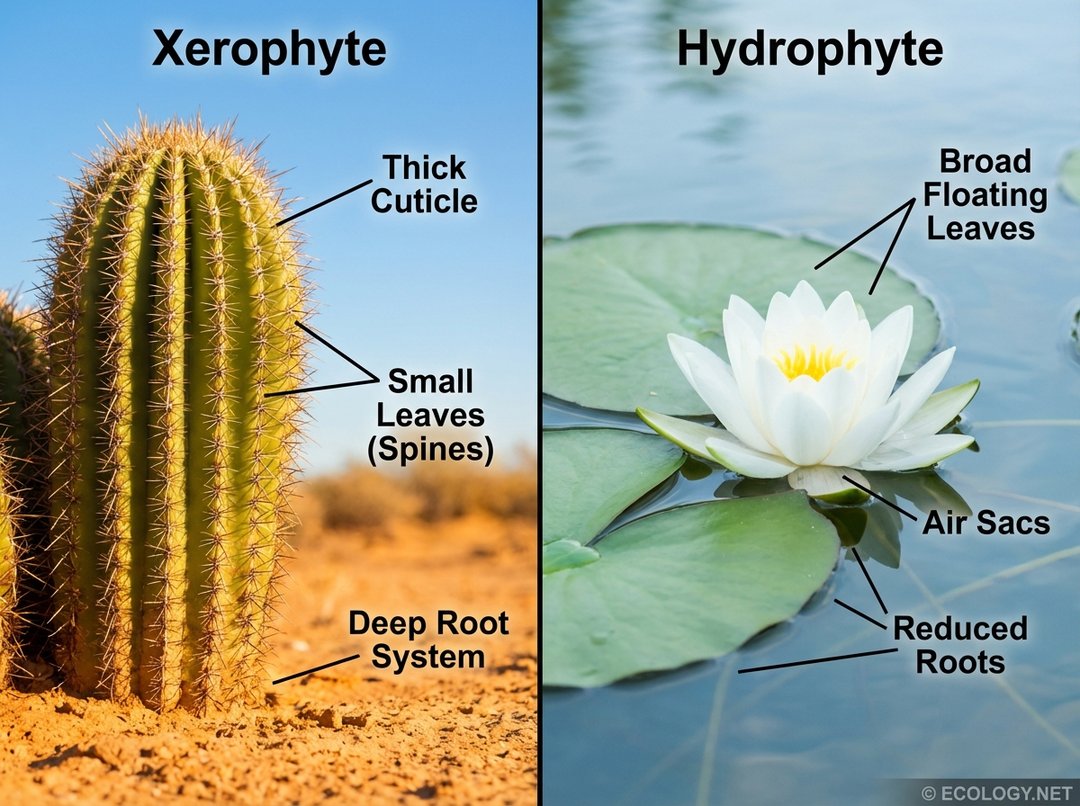

Plants have evolved an astonishing array of adaptations to manage transpiration, allowing them to thrive in diverse environments, from scorching deserts to submerged aquatic habitats.

- Xerophytes: Masters of Water Conservation

These are plants adapted to dry or arid conditions (e.g., cacti, succulents, desert shrubs). Their adaptations aim to minimize water loss:- Thick, Waxy Cuticle: A very thick outer layer to prevent evaporation.

- Reduced Leaf Surface Area: Small leaves, spines (modified leaves), or no leaves at all (stems perform photosynthesis).

- Sunken Stomata: Stomata located in pits or grooves, often lined with hairs, to create a humid microenvironment and reduce air movement.

- CAM Photosynthesis: Some desert plants open stomata at night to collect CO2 and close them during the day, drastically reducing water loss.

- Extensive Root Systems: Deep or widespread roots to maximize water absorption.

- Hydrophytes: Living in Abundance

These are plants adapted to aquatic environments, either submerged or floating (e.g., water lilies, pondweeds). Their challenge is not water scarcity, but sometimes gas exchange or excess water:- Stomata on Upper Leaf Surface: For floating leaves, stomata are on the top to facilitate gas exchange with the atmosphere. Submerged plants may lack stomata entirely.

- Thin or Absent Cuticle: No need for a thick waxy layer as water loss is not an issue.

- Large Air Spaces (Aerenchyma): To provide buoyancy and facilitate gas diffusion within the plant.

- Finely Dissected Leaves: For submerged plants, this increases surface area for nutrient and gas absorption directly from the water.

- Mesophytes: The Middle Ground

Most common plants, like garden vegetables and deciduous trees, are mesophytes. They are adapted to environments with moderate water availability and have a balance of features to manage transpiration effectively, opening stomata when water is plentiful and closing them during dry spells.

Transpiration in Agriculture and Ecology

Understanding transpiration is not just an academic exercise; it has profound implications for agriculture and ecological management.

- Agricultural Water Management: Farmers monitor transpiration rates to optimize irrigation schedules, ensuring crops receive enough water without wasteful over-irrigation. Knowledge of crop-specific transpiration helps in selecting appropriate crops for different climates.

- Forests and Regional Climate: Large forests, particularly tropical rainforests, are massive engines of transpiration. The water vapor they release contributes significantly to atmospheric moisture, influencing local and regional rainfall patterns and moderating temperatures. Deforestation can disrupt these vital ecological services.

- Climate Change Impacts: Changes in temperature, CO2 levels, and precipitation patterns due to climate change directly impact transpiration rates. This can stress plants, alter ecosystem water balances, and affect agricultural productivity worldwide.

Transpiration, often overlooked, is a testament to the intricate and powerful processes that sustain life on our planet. From the microscopic pores on a leaf to the vast expanse of a forest, the movement of water through plants is a silent symphony, orchestrating nutrient delivery, temperature regulation, and even the very climate we experience. It is a constant reminder of the interconnectedness of all living things and the environment they inhabit.