The Microscopic Marvels: Unveiling the Secrets of Stomata

Imagine a plant, silently standing in the sun, absorbing light and growing. This seemingly passive process is, in fact, a bustling hub of activity, orchestrated by countless tiny, invisible gateways on its surface. These microscopic structures, known as stomata, are the unsung heroes of the plant world, performing a delicate balancing act essential for life on Earth. Without them, plants could not breathe, photosynthesize, or regulate their internal environment, profoundly impacting everything from the food we eat to the air we breathe.

This article will journey into the fascinating world of stomata, exploring their structure, function, and the intricate mechanisms that allow them to control the flow of gases and water. Prepare to discover the vital role these tiny pores play in plant survival and global ecosystems.

What are Stomata and Where are They Found?

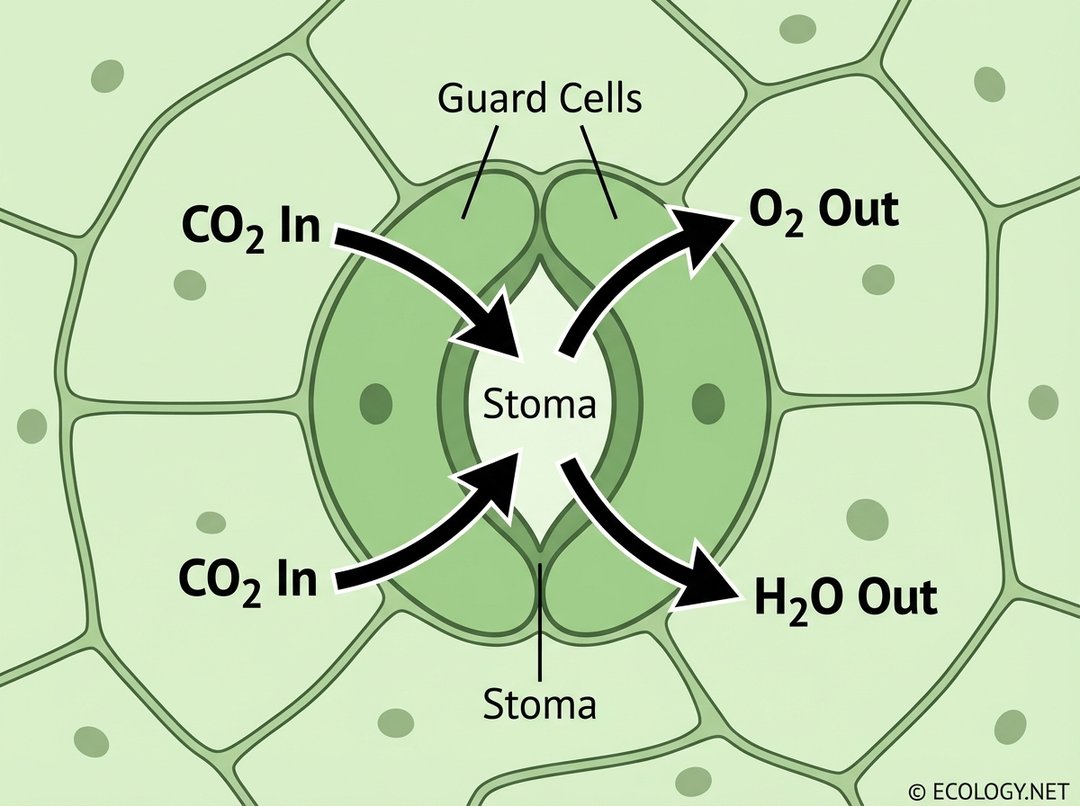

At its core, a stoma (plural: stomata) is a tiny pore, or opening, found predominantly on the surface of plant leaves, though they can also appear on stems and other aerial parts. Each stoma is not just a simple hole; it is a sophisticated gateway flanked by two specialized cells called guard cells. These guard cells are the true architects of stomatal function, capable of changing shape to open and close the pore, thereby regulating the exchange of gases and water vapor between the plant’s interior and the surrounding atmosphere.

While present on various parts of a plant, stomata are most abundant on the underside of leaves. This strategic placement helps to minimize direct exposure to sunlight and wind, which in turn reduces excessive water loss through transpiration. A typical leaf can host thousands, even millions, of these microscopic structures per square centimeter, each one diligently performing its vital duties.

This image visually introduces the basic structure of a stoma and its primary function of gas exchange, as explained in the ‘What are Stomata and Where are They Found?’ section.

To truly appreciate their prevalence, one needs a microscope. What appears as a smooth leaf surface to the naked eye transforms into a landscape dotted with these intricate pores under magnification. Their presence is a testament to nature’s efficiency, allowing plants to interact with their environment on a cellular level.

This image provides a concrete, photo-realistic visual of where stomata are primarily found on a leaf, reinforcing the concept that they are microscopic structures on the plant’s surface, as discussed in ‘What are Stomata and Where are They Found?’.

Guard Cells: The Gatekeepers in Action

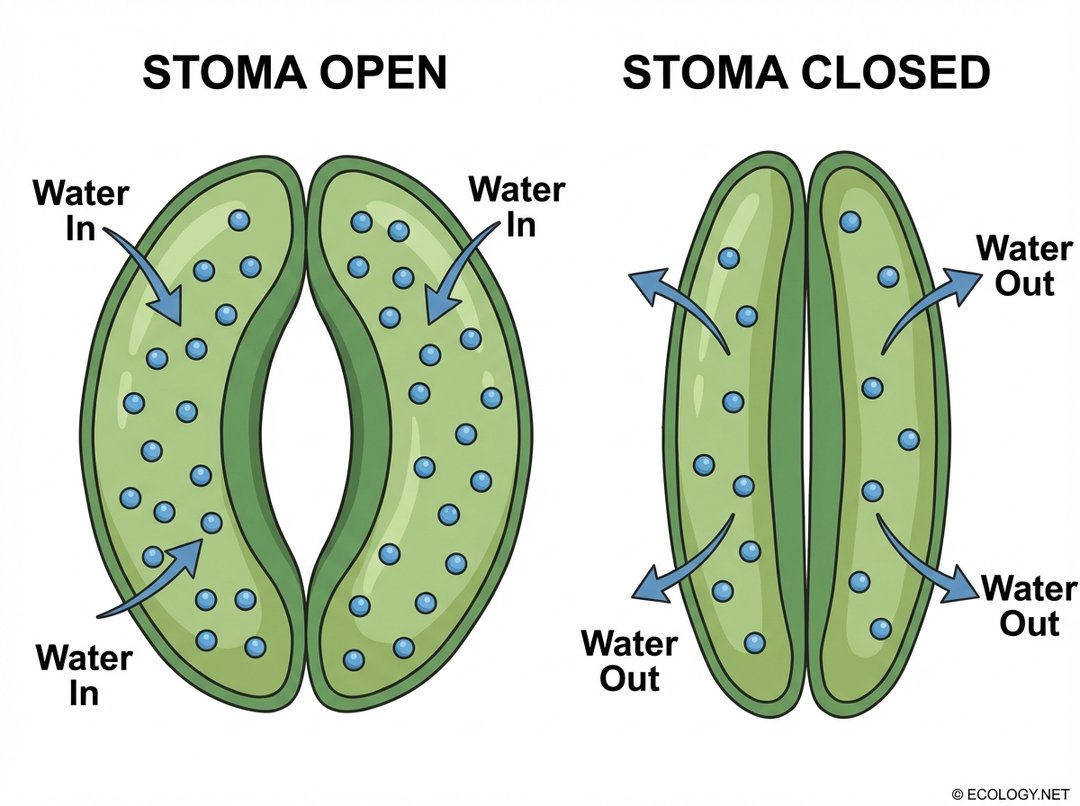

The magic of stomatal regulation lies entirely with the guard cells. These kidney-shaped cells are unique in their ability to swell and shrink, thereby controlling the size of the stomatal pore. This fascinating interplay of physics and biology is driven primarily by water movement.

The Mechanism of Opening and Closing

- Stoma Open: When conditions are favorable for photosynthesis, such as during daylight hours with sufficient water availability, guard cells actively take in water. This influx of water increases their internal pressure, known as turgor pressure. Due to the unique structure of guard cells, with thicker inner walls and thinner outer walls, this increased pressure causes them to bow outwards, creating an open pore. This allows carbon dioxide to enter for photosynthesis and oxygen to exit.

- Stoma Closed: Conversely, when the plant needs to conserve water, perhaps during drought conditions or at night, guard cells lose water. As water leaves the cells, their turgor pressure decreases, causing them to become flaccid and straighten. This change in shape brings the guard cells together, effectively closing the stomatal pore. This closure minimizes water loss through transpiration, a crucial survival mechanism.

This dynamic control allows plants to optimize their gas exchange while minimizing water loss, a constant trade-off that plants must manage to thrive.

This diagram clearly illustrates the ‘fascinating interplay of physics and biology’ behind how guard cells regulate stomatal opening and closing, as detailed in the ‘Guard Cells: The Gatekeepers in Action’ section.

The Crucial Functions of Stomata

Stomata are far more than just simple holes; they are multifunctional organs vital for plant life and, by extension, for all life on Earth.

1. Gas Exchange: The Breath of Life

The most fundamental role of stomata is facilitating gas exchange. Plants require carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere for photosynthesis, the process by which they convert light energy into chemical energy (sugars). Stomata provide the primary entry point for CO2 into the leaf’s internal tissues. Simultaneously, oxygen (O2), a byproduct of photosynthesis, exits the leaf through these same pores. This continuous exchange is critical for maintaining the atmospheric balance of these gases.

Think of stomata as the lungs of the plant, constantly inhaling carbon dioxide and exhaling oxygen, sustaining both the plant and the broader ecosystem.

2. Transpiration: The Plant’s Water Pump

Another critical function of stomata is transpiration, the process by which water vapor is released from the plant into the atmosphere. While it might seem counterintuitive for a plant to intentionally lose water, transpiration serves several vital purposes:

- Nutrient Transport: As water evaporates from the leaves, it creates a negative pressure, or “pull,” that draws water and dissolved minerals up from the roots through the xylem vessels. This continuous flow ensures that essential nutrients reach all parts of the plant.

- Cooling: The evaporation of water has a cooling effect on the plant, much like sweating cools animals. This is particularly important for plants in hot environments, preventing overheating and damage to delicate cellular machinery.

- Maintaining Turgor: While transpiration involves water loss, the overall movement of water through the plant helps maintain turgor pressure in cells, keeping the plant rigid and upright.

The regulation of transpiration is a delicate balance. Too much water loss can lead to wilting and death, while too little can hinder nutrient uptake and cooling. Stomata are the primary regulators of this process, opening and closing to adjust the rate of water vapor release.

Factors Influencing Stomatal Behavior

The opening and closing of stomata are not random events; they are finely tuned responses to a variety of environmental cues and internal signals. Plants have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to optimize stomatal function under changing conditions.

- Light Intensity: Light is the most significant stimulus for stomatal opening. In most plants, stomata open in the presence of light to allow CO2 uptake for photosynthesis and close in the dark to conserve water. Blue light is particularly effective at triggering stomatal opening.

- Carbon Dioxide Concentration: When CO2 levels inside the leaf are low (indicating high photosynthetic activity), stomata tend to open wider to allow more CO2 in. Conversely, high internal CO2 concentrations can signal stomata to close, reducing water loss when CO2 is not a limiting factor.

- Humidity: Low atmospheric humidity increases the water potential gradient between the leaf and the air, leading to higher rates of transpiration. To prevent excessive water loss, stomata tend to close in very dry conditions. High humidity, on the other hand, can encourage opening.

- Temperature: Moderate temperatures generally favor stomatal opening. Extremely high temperatures can lead to increased transpiration rates, prompting stomata to close to conserve water, even if it means reducing photosynthesis. Very low temperatures can also inhibit opening.

- Water Availability: Perhaps the most critical factor, water stress (drought) is a powerful signal for stomatal closure. When a plant experiences a shortage of water, it produces a hormone called abscisic acid (ABA), which signals the guard cells to lose turgor and close the stomata, prioritizing water conservation over photosynthesis.

- Plant Hormones: Beyond ABA, other plant hormones can also influence stomatal behavior, playing roles in growth, development, and stress responses that indirectly affect stomatal function.

Stomata in Different Environments: Adaptations and Strategies

The remarkable adaptability of plants is often reflected in their stomatal characteristics. Different environments present unique challenges, and plants have evolved diverse strategies to optimize their stomatal function for survival.

- Xerophytes (Desert Plants): Plants adapted to arid environments, such as cacti and succulents, exhibit several stomatal adaptations to minimize water loss:

- Sunken Stomata: Stomata are often located in pits or depressions on the leaf surface, creating a humid microenvironment that reduces the water potential gradient and slows transpiration.

- Thick Cuticle: A thick, waxy layer on the leaf surface further reduces non-stomatal water loss.

- Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) Photosynthesis: Many desert plants employ CAM photosynthesis, where stomata open only at night to collect CO2 (when temperatures are cooler and humidity is higher) and close during the day to conserve water.

- Reduced Leaf Surface Area: Some xerophytes have small or modified leaves (like spines) to reduce the total surface area available for transpiration.

- Hydrophytes (Aquatic Plants): Plants living in water or very wet environments have different needs:

- Floating Leaves: For plants with leaves floating on the water surface (e.g., water lilies), stomata are typically found only on the upper surface, as the underside is submerged.

- Submerged Leaves: Many fully submerged aquatic plants lack stomata entirely, absorbing gases directly through their epidermal cells.

- Mesophytes (Temperate Plants): Most common plants found in temperate regions, like many trees and garden plants, are mesophytes. They have stomata primarily on the underside of their leaves, a balanced approach to gas exchange and water conservation in environments with moderate water availability.

The Bigger Picture: Stomata and Global Ecosystems

The seemingly small actions of individual stomata collectively have profound impacts on global processes.

- Climate Regulation: Through transpiration, stomata contribute significantly to the global water cycle, releasing vast amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere, which influences cloud formation and precipitation patterns. They also play a role in regulating atmospheric CO2 levels, a key greenhouse gas.

- Agriculture and Food Security: Understanding stomatal behavior is crucial for agriculture. Plant breeders and agronomists work to develop crop varieties with stomatal characteristics that enhance water use efficiency, allowing plants to thrive in drought-prone areas or produce higher yields with less irrigation. Optimizing stomatal function can mean the difference between a bountiful harvest and crop failure.

- Evolutionary Significance: The evolution of stomata was a pivotal moment in plant history, enabling plants to colonize land by providing a controlled mechanism for gas exchange while managing water loss. This innovation paved the way for the diversification of terrestrial plant life and, consequently, the evolution of all land-dwelling organisms.

Conclusion

From the arid deserts to lush rainforests, the humble stoma stands as a testament to nature’s ingenious design. These microscopic gateways, controlled by their vigilant guard cells, perform a delicate dance of opening and closing, orchestrating the vital exchange of gases and water that sustains plant life. Their influence extends far beyond the individual leaf, impacting global climate, agricultural productivity, and the very air we breathe.

Next time you admire a vibrant green leaf, take a moment to appreciate the unseen world of stomata, diligently working to keep our planet alive and thriving. They are truly the unsung heroes of the plant kingdom, embodying the intricate beauty and profound importance of biological processes.