The natural world is a tapestry woven with countless forms of life, each playing a unique role in the grand ecological drama. To make sense of this incredible diversity, scientists have long sought to categorize and understand the fundamental units of life. At the heart of this endeavor lies one of biology’s most enduring and surprisingly complex concepts: the “species.”

For many, a species seems like an obvious distinction. A dog is a dog, a cat is a cat. But delve a little deeper, and the lines begin to blur, revealing a fascinating world of evolutionary processes, genetic nuances, and ongoing scientific debate. Understanding what defines a species is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for conservation, medicine, agriculture, and our fundamental grasp of life on Earth.

The Cornerstone: The Biological Species Concept

Perhaps the most widely recognized definition of a species, particularly in the animal kingdom, is the Biological Species Concept (BSC). Proposed by evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, the BSC defines a species as a group of individuals who can naturally interbreed and produce fertile offspring. The key here is “fertile offspring.” If two groups can mate but their progeny are sterile, they are considered distinct species.

A classic example that beautifully illustrates the BSC involves two familiar farm animals:

Consider the majestic horse (Equus caballus) and the sturdy donkey (Equus asinus). While they can mate and produce offspring, their progeny, known as mules (Equus mulus), are almost always sterile. Mules possess an odd number of chromosomes, which prevents their reproductive cells from dividing properly during meiosis. This inability to produce fertile offspring means that horses and donkeys, despite their ability to hybridize, remain distinct species under the BSC.

Limitations of the Biological Species Concept

While powerful, the BSC is not without its challenges. It struggles to classify:

- Asexual Organisms: Bacteria, archaea, and many plants and fungi reproduce without mating, making the “interbreeding” criterion irrelevant.

- Fossil Species: It is impossible to observe reproductive behavior or fertility in extinct organisms.

- Hybridization in Nature: Some distinct species can occasionally interbreed and produce fertile offspring in the wild, blurring the lines. For example, some duck species can produce fertile hybrids.

- Geographically Separated Populations: It is difficult to assess if two populations that never encounter each other would be able to interbreed.

Beyond Interbreeding: Other Ways to Define a Species

Given the limitations of the BSC, scientists have developed other species concepts, each offering a different lens through which to view biodiversity. These alternative concepts are often more applicable in specific contexts or for certain types of organisms.

The Morphological Species Concept

This is perhaps the oldest and most intuitive concept. It defines a species based on shared physical characteristics, or morphology. If individuals look alike, they are considered the same species. This concept is incredibly practical for field biologists, paleontologists, and museum curators, as it relies on observable traits.

- Strengths: Easy to apply, useful for fossils and asexual organisms, and often the first step in identification.

- Limitations: Can be misleading due to sexual dimorphism (males and females look different), phenotypic plasticity (environmental factors changing appearance), and the existence of cryptic species.

The Phylogenetic Species Concept

With advancements in genetic sequencing, the Phylogenetic Species Concept (PSC) has gained prominence. It defines a species as the smallest group of individuals that share a common ancestor and can be distinguished from other such groups. Essentially, it looks at evolutionary history and genetic distinctiveness.

- Strengths: Applicable to all organisms (sexual or asexual), uses objective genetic data, and can reveal hidden diversity.

- Limitations: Can lead to “over-splitting” of species, as even minor genetic differences might be considered distinct species, and requires extensive genetic data which is not always available.

The Ecological Species Concept

This concept defines a species based on its ecological niche, meaning the role it plays in its environment, including its habitat, diet, and interactions with other species. If two groups occupy distinct ecological niches, they are considered separate species.

- Strengths: Useful for understanding how species coexist and interact, and applicable to asexual organisms.

- Limitations: Defining a niche can be complex and subjective, and different species can sometimes share similar niches.

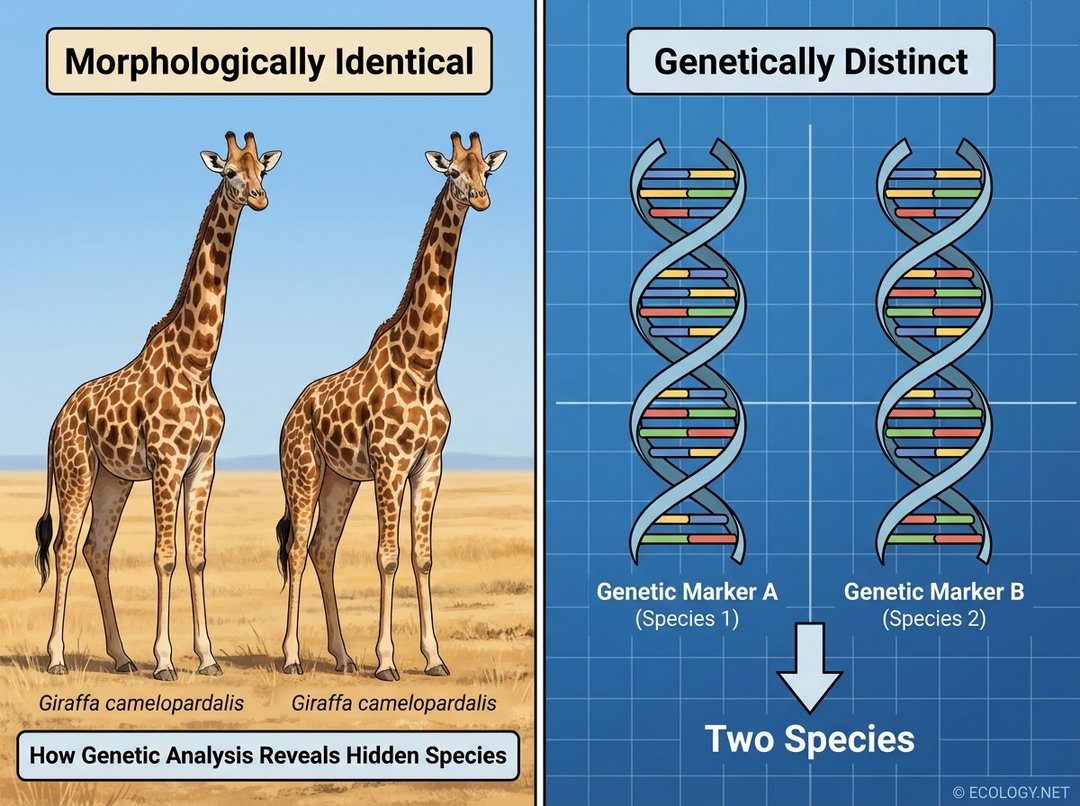

Unveiling Hidden Diversity: Cryptic Species

One of the most fascinating challenges to our traditional understanding of species comes from the phenomenon of cryptic species. These are groups of organisms that are morphologically indistinguishable or nearly so, yet are genetically distinct and reproductively isolated. They look identical to the human eye, but their DNA tells a different story.

The discovery of cryptic species has revolutionized our understanding of biodiversity. For example, what was once thought to be a single species of giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) has, through genetic analysis, been reclassified into four distinct species, each with unique genetic markers and geographic ranges. This highlights how relying solely on appearance can vastly underestimate the true richness of life on Earth. Cryptic species are found across the tree of life, from insects and amphibians to marine organisms and even mammals.

Evolution in Action: Ring Species

Another captivating example that challenges rigid species boundaries is the “ring species.” This occurs when a series of populations are distributed in a ring-like fashion around a geographic barrier, such as a mountain range or a desert. Adjacent populations in the ring can interbreed, showing a gradual change in characteristics as one moves around the circle. However, when the two ends of the ring meet, the populations are so different that they can no longer interbreed, effectively acting as distinct species.

A classic example of a ring species involves the Ensatina salamanders found around the Central Valley of California. Different populations of these salamanders interbreed with their neighbors around the valley. However, where the northern and southern ends of the ring meet in Southern California, the two forms are reproductively isolated. Ring species provide compelling evidence for gradual speciation, demonstrating how reproductive isolation can arise through a continuous series of interbreeding populations.

Why Does Defining a Species Matter?

The ongoing debate and refinement of the species concept are not just academic exercises. They have profound real-world implications:

- Conservation: Accurately identifying species is fundamental to conservation efforts. If we do not know what a species is, we cannot protect it. The discovery of cryptic species often means that what was thought to be a widespread, common species is actually several rarer, more vulnerable ones.

- Understanding Evolution: Species concepts help us understand the mechanisms of evolution and how new forms of life arise.

- Medicine and Public Health: Identifying species of pathogens, disease vectors (like mosquitoes), or parasites is crucial for developing effective treatments and control strategies.

- Agriculture: Distinguishing between crop species, wild relatives, and pests is vital for food security and pest management.

- Biodiversity Assessment: Accurate species counts are essential for assessing global biodiversity and monitoring its changes over time.

The Dynamic Nature of “Species”

The concept of a “species” is not a static, immutable definition carved in stone. Instead, it is a dynamic and evolving framework that reflects our increasing understanding of life’s complexity. From the clear-cut case of horses and donkeys to the subtle genetic distinctions of cryptic giraffes and the circular evolution of ring species, the natural world continually challenges our attempts to draw neat lines.

Ultimately, a species is a human construct, a tool we use to categorize and comprehend the immense diversity of life. While no single definition perfectly encompasses every organism, the various species concepts provide invaluable perspectives, allowing scientists to explore, understand, and protect the intricate web of life that surrounds us.