In the intricate tapestry of life, few relationships are as vital and fascinating as that between flowering plants and their pollinators. These tiny, often overlooked, heroes are the unsung architects of our ecosystems, responsible for the reproduction of nearly 90% of the world’s wild flowering plants and over 75% of the food crops we rely on. Yet, these essential creatures face unprecedented challenges, prompting a global call to action. One of the most impactful ways individuals can contribute to their survival is through the practice of pollinator gardening.

Pollinator gardening is more than just planting pretty flowers; it is a deliberate act of ecological restoration, transforming our yards, balconies, and community spaces into vibrant havens for bees, butterflies, birds, and other crucial pollinators. By understanding their needs and providing the right resources, anyone can become a steward of these invaluable species, fostering biodiversity and ensuring the health of our planet.

The Dance of Life: Understanding Pollination

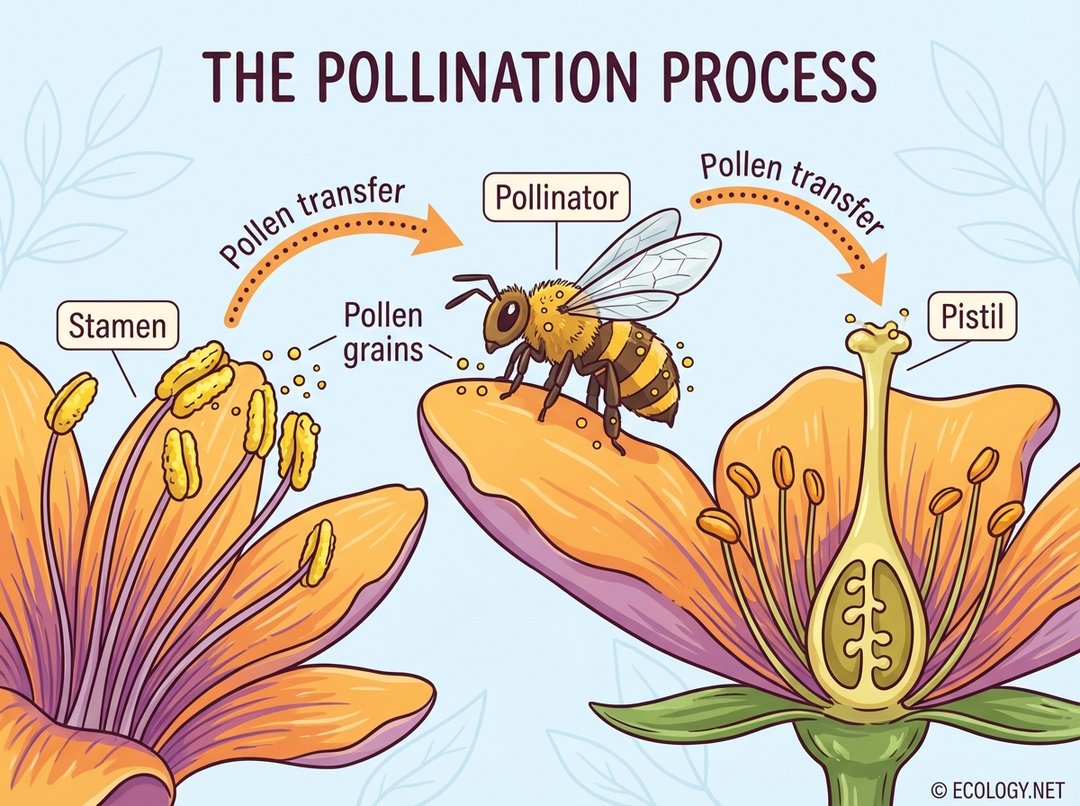

At its core, pollination is the transfer of pollen from the male part of a flower (the stamen) to the female part (the pistil), enabling fertilization and the production of seeds and fruits. While some plants are wind or water pollinated, the vast majority depend on animals to carry out this delicate task. Pollinators, in their quest for nectar and pollen, inadvertently pick up pollen grains and deposit them on other flowers, completing a cycle essential for plant reproduction and, consequently, for life on Earth.

Imagine a bee buzzing from blossom to blossom, its fuzzy body collecting microscopic golden dust. As it visits another flower, some of that dust brushes off, landing precisely where it needs to be for the plant to create new life. This seemingly simple exchange underpins the very fabric of our food systems and natural landscapes.

Who are the Pollinators?

When one thinks of pollinators, bees often come to mind first, and for good reason. Bees, particularly honeybees and bumblebees, are incredibly efficient pollinators. However, the pollinator community is far more diverse than many realize, encompassing a spectacular array of insects and even some vertebrates.

- Bees: From the familiar honeybee to the fuzzy bumblebee, and the solitary mason bee or leafcutter bee, there are over 20,000 known species of bees worldwide. They are primary pollen collectors and are often equipped with specialized hairs or “pollen baskets” to carry their precious cargo.

- Butterflies and Moths: With their long proboscises, butterflies like the iconic Monarch are excellent at reaching nectar deep within tubular flowers. Moths, often nocturnal, play a similar role under the cover of darkness.

- Birds: Hummingbirds, with their rapid wingbeats and long beaks, are key pollinators for many brightly colored, tubular flowers, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions.

- Beetles: Among the oldest pollinators, beetles are less efficient than bees but contribute significantly, especially to ancient plant lineages like magnolias.

- Flies: Hoverflies, often mistaken for bees, and other fly species are important pollinators, particularly in cooler climates or at higher altitudes.

- Other Animals: Bats, small mammals, and even some reptiles can act as pollinators in specific ecosystems, showcasing the incredible adaptability of nature.

The Urgent Need for Pollinator Gardening

Globally, pollinator populations are in decline. Habitat loss due to urbanization and agricultural expansion, the widespread use of pesticides, climate change, and the spread of diseases are all contributing factors. This decline poses a severe threat not only to natural ecosystems but also to human food security. A significant portion of our fruits, vegetables, nuts, and even coffee and chocolate depend on these diligent workers.

Pollinator gardening offers a tangible solution, creating vital stepping stones and refuges in fragmented landscapes. Every garden, no matter its size, can become a part of a larger network of pollinator pathways, providing essential food, water, and shelter.

Crafting a Pollinator Paradise: Principles and Practices

1. Plant Selection: The Buffet Approach

The cornerstone of any successful pollinator garden is thoughtful plant selection. Think of your garden as a year-round buffet, offering a continuous supply of nectar and pollen.

- Prioritize Native Plants: Native plants are adapted to local conditions and have co-evolved with native pollinators. They often provide the specific nectar and pollen compositions that local species need, and they require less water and maintenance once established. For example, milkweed is essential for Monarch butterfly caterpillars, while coneflowers and asters are magnets for various bees and butterflies.

- Diversity in Bloom Times: Ensure there are flowers blooming from early spring through late autumn. Early bloomers like crocuses and pussy willows provide crucial sustenance for emerging pollinators, while late-season flowers like goldenrod and sedum offer vital energy for those preparing for winter or migration.

- Variety in Flower Shapes and Colors: Different pollinators are attracted to different flower characteristics. Bees prefer blue, purple, white, and yellow flowers with open or shallow structures. Butterflies favor bright colors like red, orange, and purple, often with landing platforms. Hummingbirds are drawn to red, tubular flowers.

- Plant in Clumps: Grouping similar plants together creates larger, more visible targets for pollinators, making their foraging more efficient.

- Avoid “Sterile” Cultivars: Many ornamental plants have been bred for large, showy flowers or unusual colors, often at the expense of nectar and pollen production. Double-flowered varieties, for instance, can make it difficult for pollinators to access resources. Opt for single-petal varieties or those specifically labeled as pollinator-friendly.

- Host Plants for Larvae: Remember that many pollinators, especially butterflies, have specific host plants where they lay their eggs and their larvae feed. For example, parsley, dill, and fennel are host plants for swallowtail butterflies, while various willow species support many moth and butterfly caterpillars.

2. Providing Habitat: More Than Just Flowers

Pollinators need more than just food; they require safe places to nest, rest, and find shelter from the elements.

- Nesting Sites for Bees:

- Bare Ground: Approximately 70% of native bees are ground-nesters. Leave patches of undisturbed, well-drained bare soil in sunny locations.

- Wood and Stems: Many cavity-nesting bees, like mason bees, utilize hollow stems or tunnels in dead wood. Leave old plant stalks standing over winter and consider adding a “bee hotel” with varying tunnel sizes.

- Leaf Litter: A layer of leaf litter provides insulation and shelter for overwintering insects, including some queen bumblebees.

- Water Sources: Pollinators need water, especially during hot weather. A shallow dish filled with pebbles or marbles, allowing insects to drink without drowning, can be a lifesaver. Bird baths can also be adapted with stones.

- Shelter: Dense shrubs, tall grasses, and even rock piles offer protection from predators and harsh weather.

3. Garden Management: A Pollinator-Friendly Ethos

How you manage your garden is just as important as what you plant.

- Eliminate Pesticides: This is perhaps the most critical step. Insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides can be lethal to pollinators, either directly or through contaminated pollen and nectar. Embrace organic gardening practices and tolerate a certain level of insect activity.

- Embrace a Little “Messiness”: A perfectly manicured garden often lacks the natural elements pollinators need. Resist the urge to “clean up” too much. Leave fallen leaves, dead plant stalks, and brush piles.

- Reduce Mowing: If you have a lawn, consider allowing a section to grow wild or planting a pollinator-friendly lawn alternative.

- Educate and Inspire: Share your knowledge and enthusiasm with neighbors, friends, and family. Encourage them to create their own pollinator havens.

Beyond the Backyard: Advanced Pollinator Support

For those looking to deepen their impact, consider these advanced strategies:

- Creating Pollinator Corridors: Work with neighbors or community groups to establish a series of pollinator gardens that connect larger natural areas. These corridors provide safe passage and resources for pollinators moving through urban and suburban landscapes.

- Supporting Local Nurseries: Seek out nurseries that specialize in native plants and practice organic growing methods. Ask about their pesticide use to ensure you are not inadvertently bringing harmful chemicals into your garden.

- Citizen Science: Participate in pollinator monitoring programs. Documenting the types of pollinators you see in your garden contributes valuable data to scientific research, helping experts understand population trends and distribution.

A Flourishing Future

Pollinator gardening is a powerful act of hope and resilience. By transforming our personal spaces into vibrant ecosystems, we contribute to a healthier planet, one flower at a time. It is a journey of discovery, connecting us more deeply to the natural world and reminding us of the profound interconnectedness of all life. Embrace the buzz, welcome the flutter, and watch as your garden becomes a testament to the beauty and importance of these tiny, yet mighty, guardians of our global food supply and natural heritage.