Nature’s Calendar: Unlocking the Secrets of Phenology

Imagine a world where every plant and animal keeps a secret calendar, dictating when flowers bloom, birds migrate, and leaves change color. This isn’t a fantasy, but the very real, intricate dance of life governed by a fascinating scientific field known as phenology. It is the study of recurring biological events and their timing in relation to seasonal and climatic changes. From the first blush of spring blossoms to the last rustle of autumn leaves, phenology offers a window into the pulse of our planet, revealing how ecosystems respond to the subtle and not-so-subtle shifts in their environment.

What Exactly Is Phenology?

At its core, phenology is about timing. It observes and records the dates of natural events that repeat annually. Think of it as nature’s own clock, marking the progression of seasons through the observable life cycles of plants and animals. For centuries, farmers, hunters, and naturalists have intuitively practiced phenology, relying on these natural cues to guide their activities. Today, it is a critical scientific discipline, providing invaluable data for understanding ecological processes and, increasingly, for tracking the profound impacts of environmental change.

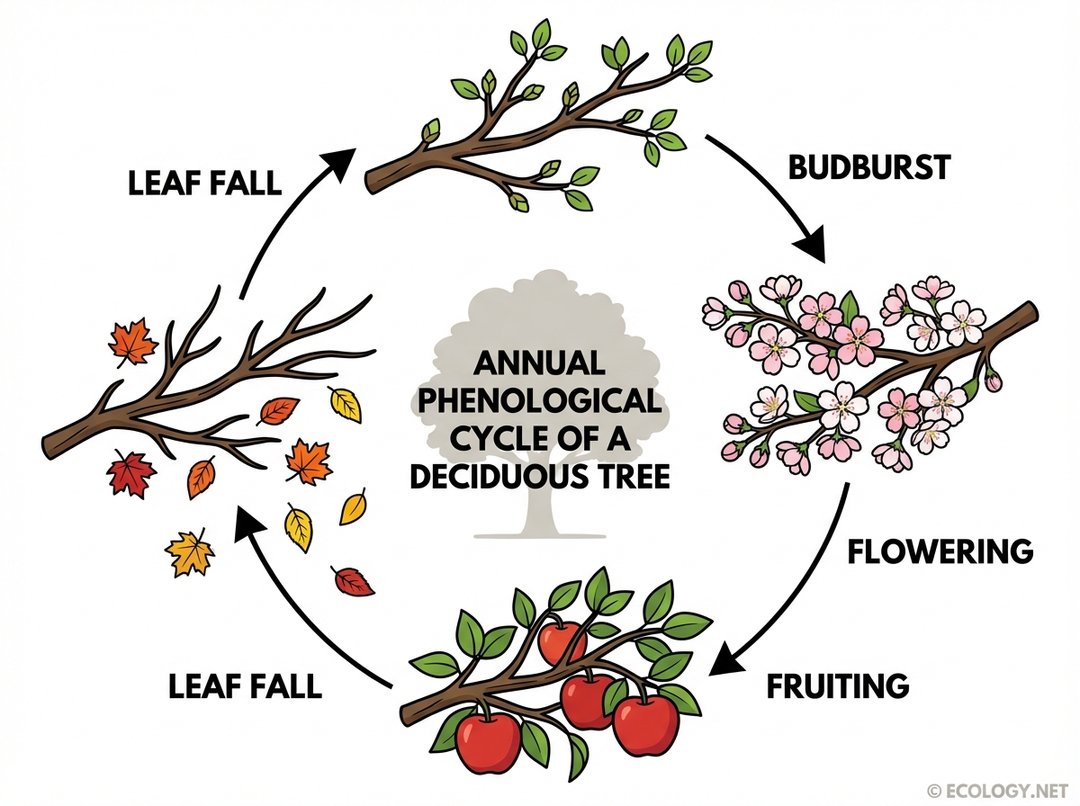

Consider a common deciduous tree in your neighborhood. Its year is a series of predictable, yet precisely timed, events:

- Budburst: The swelling and opening of buds, signaling the emergence of new leaves and flowers in spring.

- Flowering: The period when the tree produces blossoms, crucial for reproduction and attracting pollinators.

- Fruiting: The development and ripening of fruits, providing food for wildlife and dispersing seeds.

- Leaf Fall: The spectacular change in leaf color and subsequent shedding in autumn, a preparation for winter dormancy.

These stages are not random; they are carefully orchestrated by environmental cues, ensuring the tree’s survival and reproductive success.

Key Phenological Events Across Ecosystems

Phenology extends far beyond just trees. Every organism has its own set of phenological milestones. Observing these events helps scientists understand the intricate web of life.

Plant Phenology Examples:

- First Bloom: The date when a specific plant species first opens its flowers. For example, the first crocus of spring or the peak bloom of cherry blossoms.

- Leaf Out: The emergence of new leaves on deciduous trees and shrubs.

- Seed Dispersal: The period when plants release their seeds, often timed to maximize germination success.

- Senescence: The aging process of leaves leading to autumn coloration and eventual shedding.

Animal Phenology Examples:

- Migration: The arrival and departure dates of migratory birds, insects, or marine animals. Think of swallows returning in spring or monarch butterflies heading south.

- Hibernation/Estivation: The timing of animals entering or emerging from periods of dormancy. Bears emerging from their dens or frogs becoming active after winter.

- Breeding/Nesting: The start and end of reproductive cycles. The first robin’s nest or the hatching of sea turtle eggs.

- Emergence: The appearance of insects from pupae or larvae, such as the first dragonflies of summer.

The Environmental Conductors: Drivers of Phenology

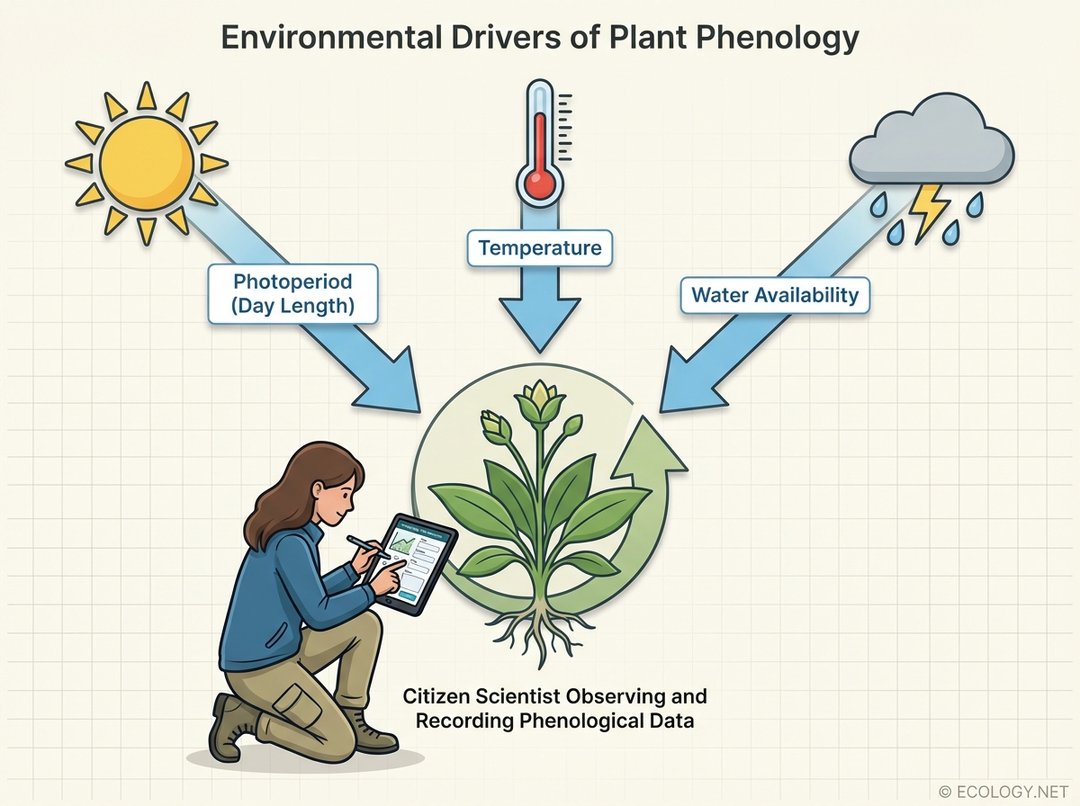

What prompts a tree to bud or a bird to migrate? The timing of phenological events is not arbitrary; it is a finely tuned response to environmental signals. Three primary drivers orchestrate nature’s calendar:

- Temperature: This is arguably the most significant driver for many organisms. Warmer temperatures in spring often trigger earlier budburst and flowering, while colder temperatures can delay these events. The accumulation of “growing degree days” is a common metric used to predict plant development.

- Photoperiod (Day Length): The duration of daylight hours provides a reliable, consistent cue, especially for events like leaf fall in autumn or the migration of birds. Unlike temperature, day length is predictable and does not fluctuate year to year in the same way.

- Water Availability: The presence or absence of water can profoundly influence plant growth and animal activity. Droughts can accelerate leaf senescence or delay flowering, while ample rainfall can spur growth.

These factors often interact in complex ways. For instance, a plant might require a certain period of cold (vernalization) followed by warming temperatures and increasing day length to break dormancy and flower.

Why Does Phenology Matter? The Ecological Ripple Effect

Understanding phenology is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for comprehending the health and functioning of ecosystems, and even for human well-being. The timing of these natural events creates a delicate balance, and shifts can have far-reaching consequences.

Ecological Interactions:

Many species have evolved to synchronize their life cycles. Pollinators, like bees and butterflies, emerge when their food sources, flowering plants, are abundant. Herbivores time their breeding to coincide with the flush of new, nutritious plant growth. Predators often time their hunting to the availability of their prey. When these timings get out of sync, the consequences can be severe.

Agriculture and Food Security:

Farmers rely heavily on phenological cues to know when to plant, irrigate, and harvest crops. Shifts in phenology can impact crop yields, alter pest cycles, and even affect the suitability of certain regions for specific crops. For example, an early spring frost after fruit trees have bloomed can devastate an entire harvest.

Human Health:

Phenology influences aspects of human health, from the timing and intensity of allergy seasons due to pollen release, to the activity patterns of disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes and ticks. Earlier springs can mean longer allergy seasons and extended periods of vector-borne disease risk.

Phenology and Climate Change: A Shifting Calendar

Perhaps the most critical reason phenology matters today is its role as a sensitive indicator of climate change. As global temperatures rise, the natural calendar is shifting, often with profound implications.

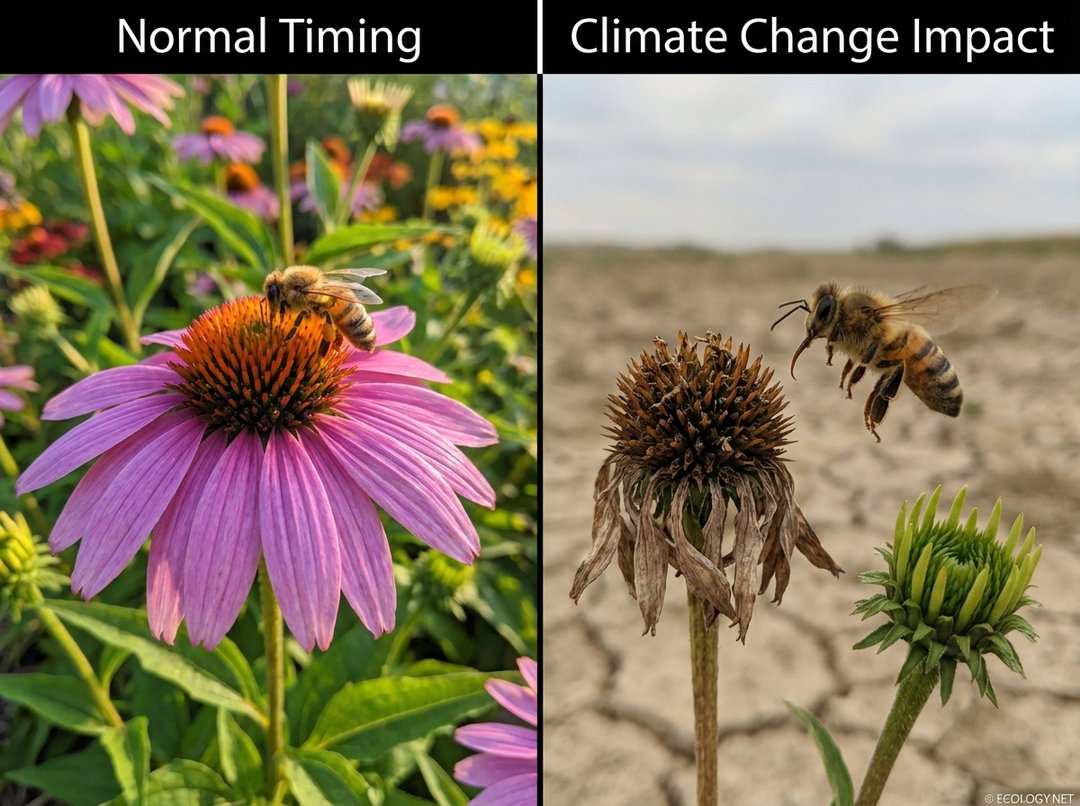

The Phenomenon of Phenological Mismatch:

One of the most concerning impacts of climate change on phenology is the creation of “phenological mismatches.” This occurs when the timing of interdependent species shifts at different rates, disrupting critical ecological interactions. For example:

- If a plant flowers earlier due to warmer temperatures, but its specific pollinator emerges at its traditional time, the pollinator might miss the bloom, leading to reduced plant reproduction and a lack of food for the pollinator.

- Migratory birds might arrive at their breeding grounds to find that their insect food source has already peaked and declined, leaving them with insufficient sustenance for their young.

- Predators might find their prey populations have already dispersed or matured beyond an easily catchable stage by the time they are ready to hunt.

These mismatches can lead to declines in populations, reduced biodiversity, and even ecosystem collapse if the disruptions are severe and prolonged.

The delicate balance of nature relies on precise timing. When climate change alters this timing, the intricate dance between species can fall out of step, creating a cascade of ecological challenges.

Citizen Science: Everyone Can Be a Phenologist

The study of phenology requires vast amounts of data collected over long periods and across wide geographical areas. This is where citizen science plays an invaluable role. Ordinary people, with a keen eye for nature, can contribute significantly to our understanding of phenological shifts.

- By observing and recording the dates of events like the first robin of spring, the blooming of a local lilac bush, or the changing colors of autumn leaves, citizen scientists provide crucial data points.

- Organizations worldwide facilitate these observations, allowing individuals to submit their findings to large databases. This collective effort creates comprehensive datasets that scientists use to track trends, identify changes, and make predictions about future ecological responses to climate change.

Participating in citizen science projects is a powerful way to connect with nature, learn about local ecosystems, and contribute to vital scientific research that informs conservation efforts and climate change adaptation strategies.

The Future of Phenology: Prediction and Adaptation

The data gathered through phenological observations is not just for understanding the past; it is critical for predicting the future. Scientists use phenological models to forecast how ecosystems might respond to continued climate change, helping to inform conservation strategies, agricultural planning, and resource management.

- For instance, understanding the timing of pest emergence can help farmers implement targeted, environmentally friendly pest control measures.

- Predicting the timing of pollen release can help public health officials issue warnings for allergy sufferers.

- Identifying species particularly vulnerable to phenological mismatches can guide conservation efforts to protect them.

As our planet continues to experience rapid environmental shifts, the study of phenology becomes ever more important. It provides the essential knowledge needed to anticipate challenges and develop strategies for adaptation, ensuring the resilience of both natural and human systems.

Conclusion

Phenology reminds us that nature operates on a precise, yet dynamic, calendar. By observing the subtle cues of budburst, migration, and leaf fall, we gain profound insights into the interconnectedness of life and the powerful influence of our environment. In an era of rapid climate change, phenology serves as a vital barometer, signaling shifts that demand our attention and action. Becoming a phenologist, even in a small way, offers a deeper appreciation for the natural world and empowers us to be more informed stewards of our planet.