The Grand Architect of Life: Understanding Natural Selection

Imagine a world teeming with life, from the smallest microbe to the largest whale. Every creature, in its unique form and function, is a testament to an extraordinary process that has shaped existence over billions of years. This process, elegant in its simplicity yet profound in its impact, is known as natural selection. Far from a random occurrence, natural selection is the guiding force behind evolution, meticulously sculpting species to fit their environments with astonishing precision. It is the engine that drives biodiversity, creating the breathtaking array of life we see today and continuously adapting it to an ever-changing planet.

The Basic Principles: How Natural Selection Works

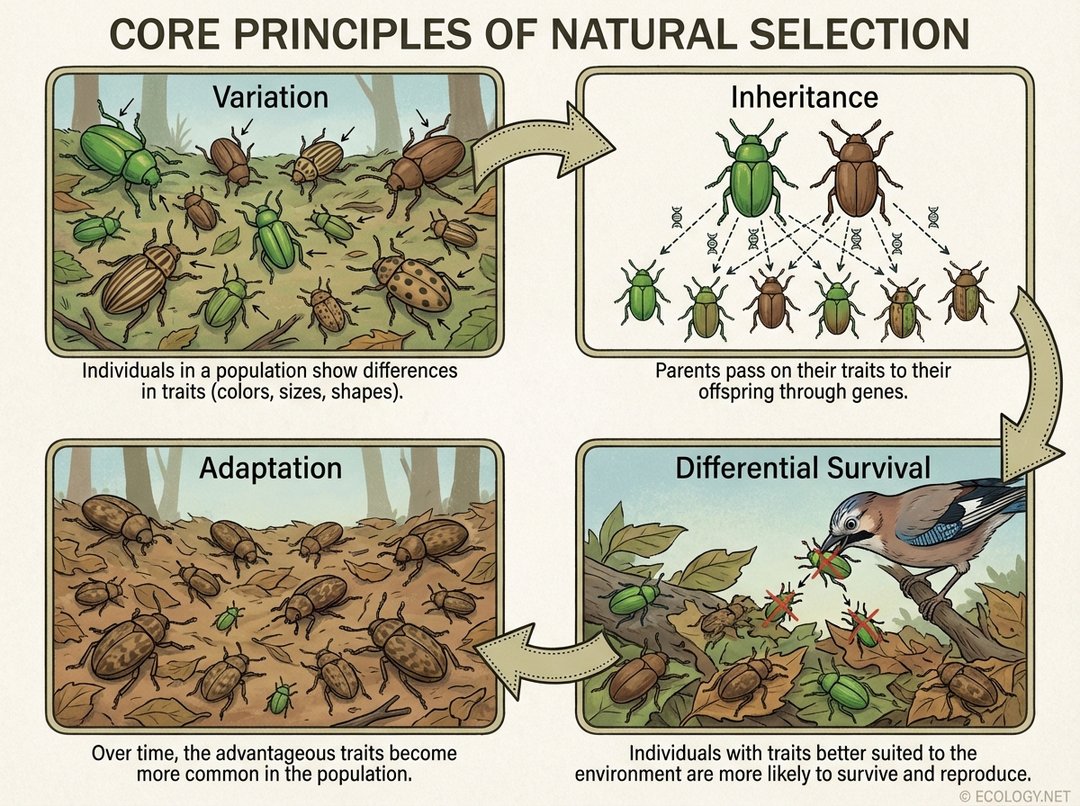

At its core, natural selection operates on a few fundamental principles. Understanding these building blocks is key to grasping the immense power of this evolutionary mechanism.

Here are the four pillars upon which natural selection stands:

- Variation: Within any population of organisms, individuals are not identical. They exhibit a range of traits, from differences in size and color to variations in behavior and resistance to disease. This inherent diversity is the raw material for natural selection.

- Inheritance: Many of these variations are heritable, meaning they can be passed down from parents to their offspring. Traits are encoded in an organism’s genetic material, ensuring that advantageous characteristics can persist across generations.

- Differential Survival and Reproduction: Resources in any environment are limited, leading to a “struggle for existence.” Not all individuals survive to reproduce, and among those that do, some will produce more offspring than others. Individuals with traits that make them better suited to their environment are more likely to survive, thrive, and pass on those advantageous traits.

- Adaptation: Over successive generations, as individuals with beneficial traits consistently out-reproduce those without them, the frequency of these advantageous traits increases in the population. This gradual accumulation of favorable characteristics leads to adaptation, where a species becomes increasingly well-suited to its specific ecological niche.

These principles work in a continuous loop, constantly refining populations. It is not a conscious choice by organisms, but rather an automatic outcome of the interaction between individuals and their environment.

This image visually breaks down the foundational principles of natural selection, making the abstract concepts of variation, inheritance, differential survival, and adaptation easy to understand through a clear, sequential diagram.

Classic Examples of Natural Selection in Action

To truly appreciate natural selection, it helps to examine real-world examples where its effects are clearly visible. These case studies provide compelling evidence of evolution in progress.

The Peppered Moths and Industrial Melanism

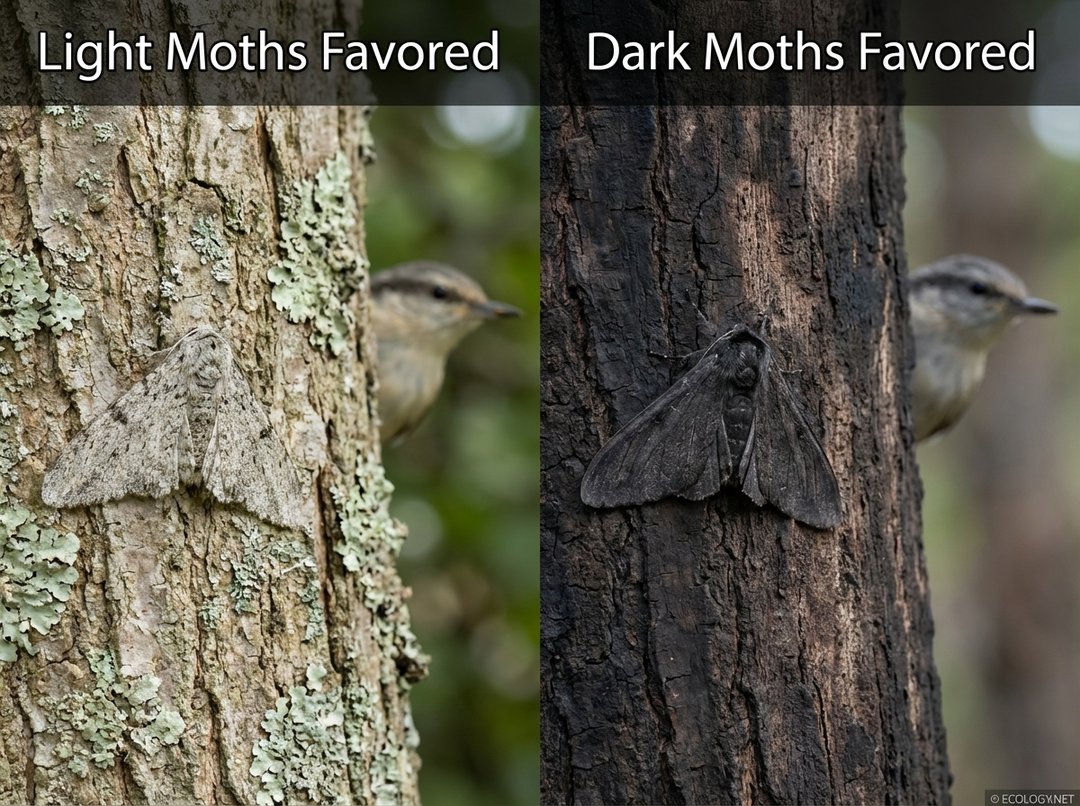

One of the most famous and striking examples of natural selection is found in the peppered moth (Biston betularia) in England. Before the Industrial Revolution, light-colored peppered moths were common. Their mottled, pale wings provided excellent camouflage against lichen-covered tree trunks, protecting them from predatory birds. Darker variants, though present, were rare because they stood out against the light bark and were easily picked off.

However, as industrialization swept across Britain, coal-burning factories released vast amounts of soot into the atmosphere. This pollution darkened tree trunks and killed off the light-colored lichens. Suddenly, the environment shifted dramatically. The light-colored moths, once camouflaged, now stood out starkly against the blackened trees, making them easy targets for birds. The previously rare dark-colored moths, on the other hand, became perfectly camouflaged. Over a relatively short period, the population of peppered moths underwent a dramatic change: dark moths became far more prevalent than light moths.

This image provides a compelling, photo-realistic example of natural selection in action, demonstrating how environmental changes drive adaptation in the peppered moth population.

When pollution controls were introduced in the late 20th century, tree trunks began to lighten again, and remarkably, the population of light-colored moths started to rebound. This cyclical change perfectly illustrates how natural selection is a dynamic process, constantly responding to environmental pressures.

Darwin’s Finches: Beak Adaptations in the Galapagos

Charles Darwin’s observations of finches on the Galapagos Islands were pivotal in his development of the theory of natural selection. He noticed that while the finches on different islands were clearly related, they exhibited remarkable variations in their beak shapes and sizes. These differences were not random; each beak was exquisitely adapted to the specific food sources available on its particular island.

- Finches with large, robust beaks were adept at cracking open tough seeds.

- Those with slender, pointed beaks were skilled at probing for insects in crevices.

- Finches with longer, slightly curved beaks could extract nectar from flowers.

This image illustrates another classic example, visually demonstrating how natural selection leads to diverse adaptations, such as beak shapes, for different ecological niches within a single group of organisms.

Darwin realized that these specialized beaks were not created for their purpose, but rather, individuals born with beaks better suited to the available food sources on their island were more successful at feeding, surviving, and reproducing. Over many generations, this differential success led to the diversification of finch species, each perfectly tailored to its unique dietary niche.

Other Powerful Examples

- Antibiotic Resistance: The rapid evolution of bacteria resistant to antibiotics is a stark, modern example. When antibiotics are used, they kill susceptible bacteria, but any bacteria with a natural resistance mutation survive and reproduce, passing on their resistance. This leads to populations of “superbugs” that are increasingly difficult to treat.

- Pesticide Resistance: Similarly, insects and weeds quickly evolve resistance to pesticides and herbicides. Individuals with natural immunity survive chemical treatments and pass on their resistance, leading to less effective pest control over time.

- Sickle Cell Anemia and Malaria: In regions where malaria is prevalent, individuals who are heterozygous for the sickle cell trait (carrying one copy of the gene) have increased resistance to malaria. While homozygous individuals suffer from sickle cell disease, the survival advantage for heterozygotes in malaria-prone areas maintains the gene in the population, a fascinating example of balancing selection.

Beyond the Basics: Nuances of Natural Selection

While the core principles remain constant, natural selection manifests in various forms, leading to different evolutionary outcomes.

Types of Natural Selection

- Directional Selection: This occurs when individuals at one extreme of a phenotypic range have greater fitness than individuals in the middle or at the other extreme. The peppered moth example is a classic case of directional selection, favoring darker moths in polluted environments.

- Stabilizing Selection: This type of selection favors intermediate variants and acts against extreme phenotypes. For example, human birth weight often falls within an optimal range; babies that are too small or too large have higher mortality rates.

- Disruptive Selection: In contrast to stabilizing selection, disruptive selection favors individuals at both extremes of the phenotypic range over intermediate phenotypes. This can occur in environments with diverse resources, leading to the divergence of populations and potentially new species.

Sexual Selection

A specialized form of natural selection, sexual selection, involves competition for mates. It often leads to the evolution of elaborate traits that might seem detrimental to survival, such as the peacock’s extravagant tail or the antlers of a male deer. These traits, while potentially making an individual more vulnerable to predators, enhance their chances of attracting a mate and successfully reproducing, thus increasing their overall fitness.

Natural Selection is Not Goal-Oriented

It is crucial to understand that natural selection is not a conscious process with a predetermined goal. It does not strive for “perfection” or create organisms perfectly suited for all future conditions. Instead, it is an opportunistic process, acting on the variations that are already present in a population at a given time and in a specific environment. What is advantageous today might be a disadvantage tomorrow if the environment changes.

Natural selection is a blind, mechanical process, not a benevolent designer. It simply favors traits that enhance survival and reproduction in the current environmental context.

The Profound Impact on Life on Earth

Natural selection is more than just a biological concept; it is the fundamental explanation for the diversity, complexity, and adaptation of life on Earth. It explains why organisms are so well-suited to their environments, from the streamlined body of a fish to the intricate camouflage of a chameleon. It accounts for the incredible array of species, each occupying its unique niche, and the constant dance of co-evolution between predators and prey, parasites and hosts.

Understanding natural selection provides a powerful lens through which to view the living world. It helps us comprehend the emergence of new diseases, the challenges of conservation, and even our own place in the grand tapestry of life. It is a testament to the dynamic and ever-changing nature of our planet, where life is perpetually shaped by the relentless, yet elegant, hand of natural selection.