Imagine a world where every living thing could live anywhere it wanted, with unlimited food, perfect weather, and no threats. In such a fantastical scenario, a species would occupy its absolute maximum potential living space. This theoretical ideal is what ecologists call the fundamental niche.

The fundamental niche represents the full range of environmental conditions and resources that a species could possibly use and tolerate if there were no limiting factors like predators, competitors, or diseases. It is essentially the biological blueprint of a species’ potential existence, shaped by its evolutionary history and physiological capabilities.

Unpacking the Fundamental Niche: A Species’ Potential

At its heart, the fundamental niche is about potential. It describes all the places a species could survive, grow, and reproduce successfully, given its inherent biological traits. Think of it as a species’ ultimate wish list for an ideal home.

The Pillars of a Fundamental Niche

Several key factors define the boundaries of a species’ fundamental niche:

- Physiological Tolerance: This refers to the range of physical and chemical conditions a species can endure. Every organism has limits to the temperature, humidity, pH levels, salinity, light intensity, and nutrient availability it can tolerate. For instance, a polar bear cannot survive in a desert, nor can a desert cactus thrive in the Arctic.

- Resource Requirements: What does a species need to live? This includes the type and amount of food, water, light, specific nutrients, and space required for individuals to grow and populations to sustain themselves. A koala, for example, has a fundamental niche tied to the availability of eucalyptus leaves.

- Reproductive Needs: The fundamental niche also encompasses the specific conditions necessary for successful reproduction. This might include particular nesting sites, mating rituals, or environmental cues for breeding. Salmon, for instance, require very specific freshwater conditions to spawn.

- Behavioral Adaptations: Certain behaviors, such as migration patterns, burrowing habits, or social structures, are integral to a species’ survival and thus part of its fundamental niche.

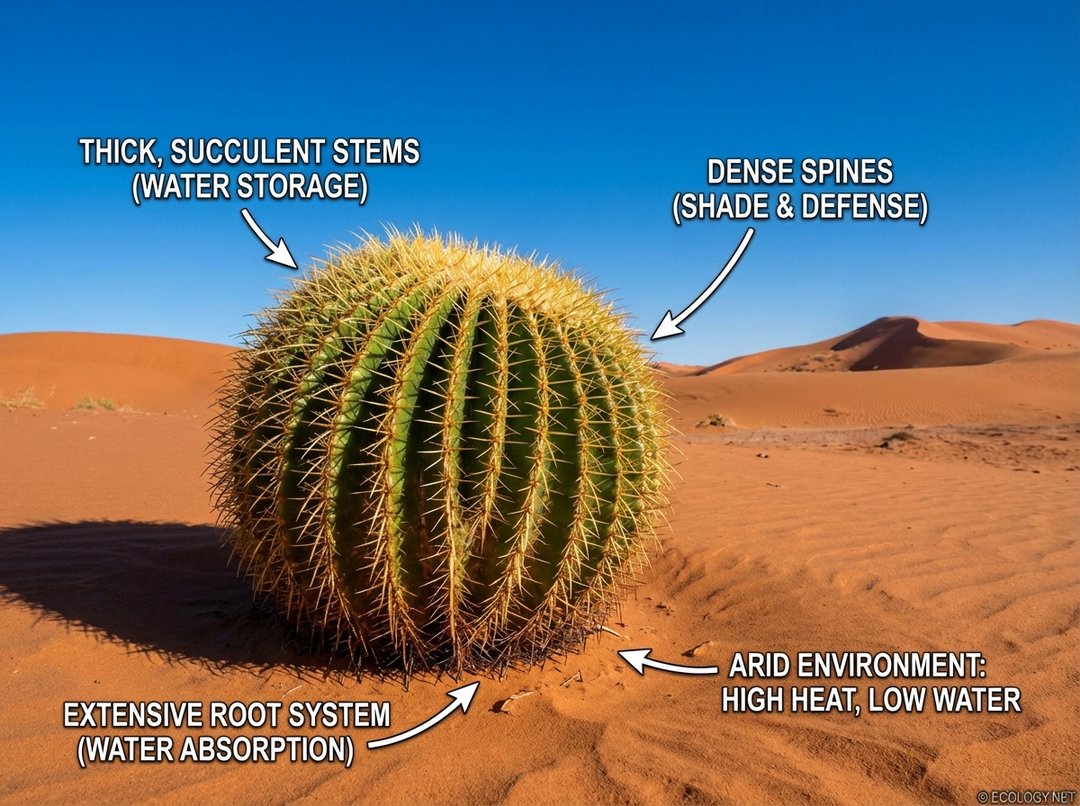

Consider the humble cactus. Its thick stems, waxy coating, and deep root systems are all adaptations that allow it to tolerate extreme heat and drought. These physiological traits define a fundamental niche that includes arid environments, even if other factors might prevent it from occupying every single desert on Earth.

From Potential to Reality: Fundamental vs. Realized Niche

While the fundamental niche outlines where a species could live, the reality is often quite different. In the natural world, species rarely get to live in their ideal, unconstrained environments. This brings us to the concept of the realized niche.

The realized niche is the actual set of environmental conditions and resources that a species occupies and uses in the presence of other species and limiting factors. It is always smaller than or equal to the fundamental niche, never larger.

Why the Discrepancy? Limiting Factors at Play

The gap between the fundamental and realized niche is created by various ecological interactions and constraints:

- Competition: When two or more species require the same limited resources (food, water, space, light), they compete. Stronger competitors can exclude a species from parts of its fundamental niche. This can be competition between different species (interspecific) or even within the same species (intraspecific).

- Predation: The presence of predators can force a prey species to avoid certain areas or times, even if those areas offer ideal resources. A deer might avoid a lush meadow if a pack of wolves frequently hunts there.

- Disease and Parasitism: Pathogens and parasites can limit a species’ distribution and abundance, preventing it from thriving in areas that would otherwise be suitable.

- Resource Scarcity: Even without direct competition, resources might simply be too scarce in certain areas to support a population, narrowing the realized niche.

- Human Impact: Habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change are increasingly powerful factors that shrink species’ realized niches, often dramatically.

Niche Differentiation and Coexistence

The concept of the fundamental and realized niche helps us understand how multiple species can coexist in the same general area. If every species tried to occupy its full fundamental niche, competition would be fierce, often leading to the exclusion of some species. Instead, species often evolve to specialize, leading to niche differentiation.

Niche differentiation occurs when species evolve to use different resources, occupy different microhabitats, or forage at different times, thereby reducing direct competition. This allows them to carve out their own realized niches within a shared environment.

A classic example comes from the Galapagos finches. Different finch species on the same island have evolved distinct beak sizes and shapes, allowing them to specialize in consuming different types of seeds. One species might have a large, strong beak for cracking tough seeds, while another has a smaller, more delicate beak for tiny seeds. This specialization minimizes direct competition for food resources.

The Ecological Significance: Why Understanding Niches Matters

Understanding the fundamental niche is not just an academic exercise; it has profound implications for conservation, management, and predicting ecological change.

- Conservation Biology: Knowing a species’ fundamental niche helps conservationists identify suitable habitats for reintroduction programs or predict which areas might be critical for a species’ survival under changing conditions. It helps define the maximum potential range for a species.

- Invasive Species Management: When an invasive species is introduced to a new environment, understanding its fundamental niche can help predict how widely it might spread and what native species it might outcompete.

- Climate Change Predictions: As global climates shift, the fundamental niches of many species are being altered. Ecologists use this concept to model how species distributions might change, identifying vulnerable populations and potential new ranges.

- Resource Management: For sustainable harvesting or management of natural resources, understanding the niche requirements of key species is crucial to ensure their long-term viability.

Beyond the Basics: The N-Dimensional Hypervolume

For a more advanced perspective, the renowned ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson provided a more formal definition of the fundamental niche in 1957. He described it as an “N-dimensional hypervolume.”

Imagine each environmental factor (temperature, humidity, food size, light intensity, etc.) as a dimension. If a species can tolerate temperatures between 10°C and 20°C, that’s one dimension. If it also requires humidity between 50% and 70%, that’s a second dimension. Add in food particle size, pH, soil type, and so on, and you create a multi-dimensional space. The “volume” within this space where the species can survive and reproduce indefinitely is its fundamental niche.

This abstract concept highlights that a species’ niche is not just about a single factor but a complex interplay of many variables. The realized niche, then, is a smaller hypervolume within this larger fundamental hypervolume, constrained by biotic interactions.

Another related concept is the competitive exclusion principle, which states that two species cannot coexist indefinitely if they occupy exactly the same realized niche. One will eventually outcompete the other. This principle underscores the importance of niche differentiation for biodiversity.

Sometimes, competition can even lead to character displacement, where competing species evolve different traits (like the finches’ beak sizes) to reduce competition and allow for coexistence. This is a powerful example of how ecological interactions can drive evolutionary change.

Conclusion

The fundamental niche is a cornerstone concept in ecology, offering a powerful lens through which to view the potential of life on Earth. It reminds us that every species has a unique set of requirements and tolerances, a biological blueprint that dictates where it could thrive. While the realized niche reflects the harsh realities of competition and environmental limits, understanding the fundamental niche provides invaluable insights into species distribution, conservation strategies, and the intricate web of life. It is a testament to the incredible diversity and adaptability of organisms, each striving to find its place in the grand tapestry of nature.