In the vibrant tapestry of the natural world, survival is a constant dance between predator and prey. While some creatures rely on camouflage to blend seamlessly into their surroundings, others boldly announce their presence with a dazzling display of color. This striking strategy, known as aposematism, is nature’s way of shouting a clear warning: “I am dangerous, do not eat me!”

Aposematism is a fascinating evolutionary adaptation where animals signal their unpalatability or toxicity to potential predators through conspicuous coloration, patterns, or even sounds. These warning signals are not meant to attract mates or impress rivals, but rather to deter hungry hunters, saving both the prey and the predator from a potentially unpleasant or even fatal encounter.

How Does Aposematism Work? The Learning Process

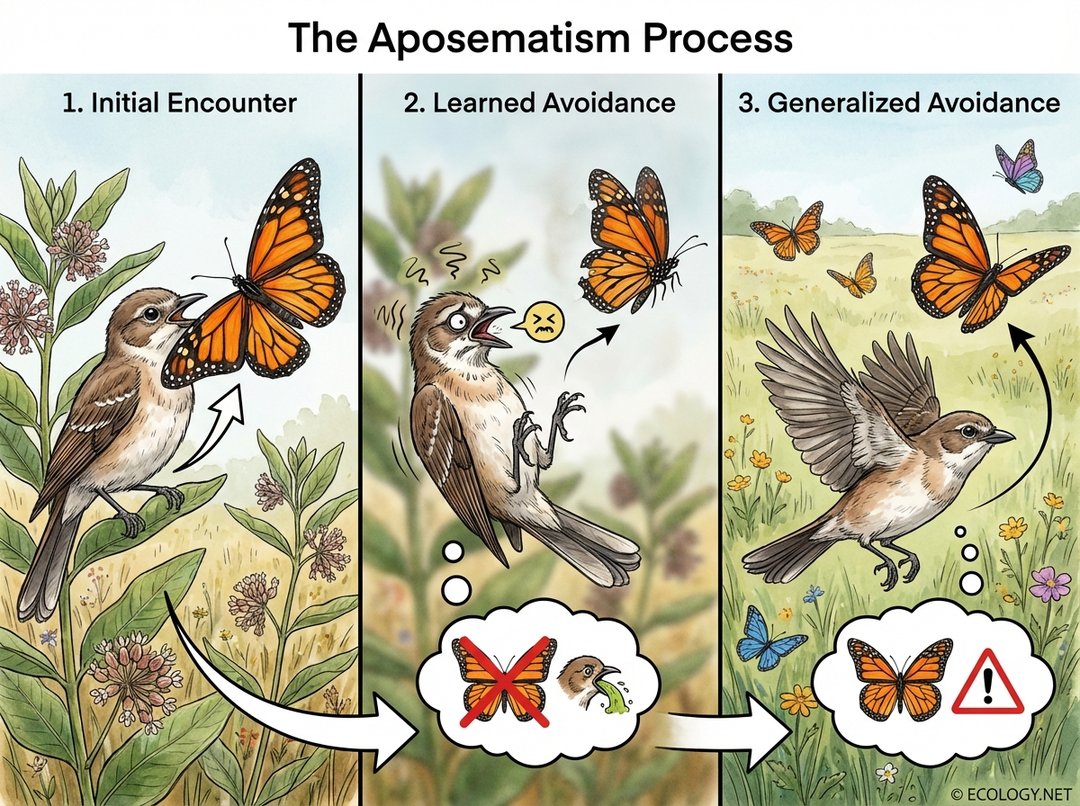

At its core, aposematism relies on a predator’s ability to learn and remember. Imagine a young, inexperienced bird encountering a brightly colored insect for the first time. Its instincts might tell it to investigate, perhaps even to take a bite. This initial encounter is crucial.

- Initial Encounter: A predator, unfamiliar with the warning signal, attempts to consume the aposematic prey.

- Negative Consequence: The predator quickly experiences an unpleasant sensation. This could be a foul taste, a burning sting, or a toxic reaction that causes illness.

- Learned Avoidance: The predator associates the distinctive warning colors or patterns with the negative experience. Its brain forms a strong memory: “Bright colors mean bad taste/danger.”

- Generalized Avoidance: In subsequent encounters, the predator recognizes the warning signal and actively avoids similar-looking prey, even if it has not encountered that specific individual before. This benefits both the individual prey and its species.

This learning process is remarkably efficient. Predators quickly learn to avoid aposematic species, often after just one or two negative experiences. This means that while a few individuals might be sacrificed in the learning curve, the vast majority of the aposematic population benefits from the collective memory of their predators.

The Science Behind the Signal: Why Bright Colors?

The effectiveness of aposematism hinges on the clarity and memorability of the warning signal. Aposematic animals typically display colors that stand out starkly against their natural backgrounds. Common warning colors include:

- Red: Often associated with danger and toxicity.

- Yellow: Another highly visible color, frequently paired with black.

- Orange: A blend of red and yellow, also very conspicuous.

- Black: Provides strong contrast when paired with bright colors, making patterns pop.

- White: Less common as a primary warning color, but can be used for contrast.

These colors are often arranged in bold, contrasting patterns such as stripes, spots, or bands. Think of the alternating black and yellow stripes of a wasp or the red, yellow, and black bands of a coral snake. These patterns are easy for predators to spot from a distance and are highly memorable, reinforcing the learned association with danger.

The evolutionary advantage of aposematism is clear: by advertising their danger, these animals avoid the costly need for physical confrontation or elaborate escape mechanisms. It is a declaration of invincibility in the face of predation.

Diverse Examples of Aposematic Animals

Aposematism is a widespread phenomenon, found across various animal kingdoms, from insects to amphibians and reptiles. Here are some classic examples:

- Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus): These iconic orange and black butterflies are a prime example. Their caterpillars feed on milkweed plants, accumulating cardenolides, a type of cardiac glycoside that is toxic to many predators. Birds that attempt to eat a monarch quickly learn to associate its vibrant colors with a bitter taste and subsequent illness.

- Poison Dart Frogs (Family Dendrobatidae): Found in the rainforests of Central and South America, these small frogs are famous for their dazzling, iridescent colors, ranging from brilliant blues and reds to vibrant yellows and greens. Their skin secretes potent neurotoxins, making them one of the most toxic animals on Earth. Their bright colors serve as an unmistakable “do not touch” sign.

- Coral Snakes (Genus Micrurus and Micruroides): These highly venomous snakes are recognized by their distinctive bands of red, yellow (or white), and black. Their warning coloration is so effective that many harmless snakes have evolved to mimic their patterns.

- Wasps and Bees (Order Hymenoptera): The familiar black and yellow stripes of many wasps and bees are a classic warning signal for their painful sting. Predators quickly learn to avoid these buzzing insects after a single encounter.

Mimicry: Exploiting the Warning Signal

The success of aposematism has led to an intriguing evolutionary phenomenon known as mimicry, where one species evolves to resemble another. In the context of warning signals, mimicry allows some species to capitalize on the established deterrents of aposematic models.

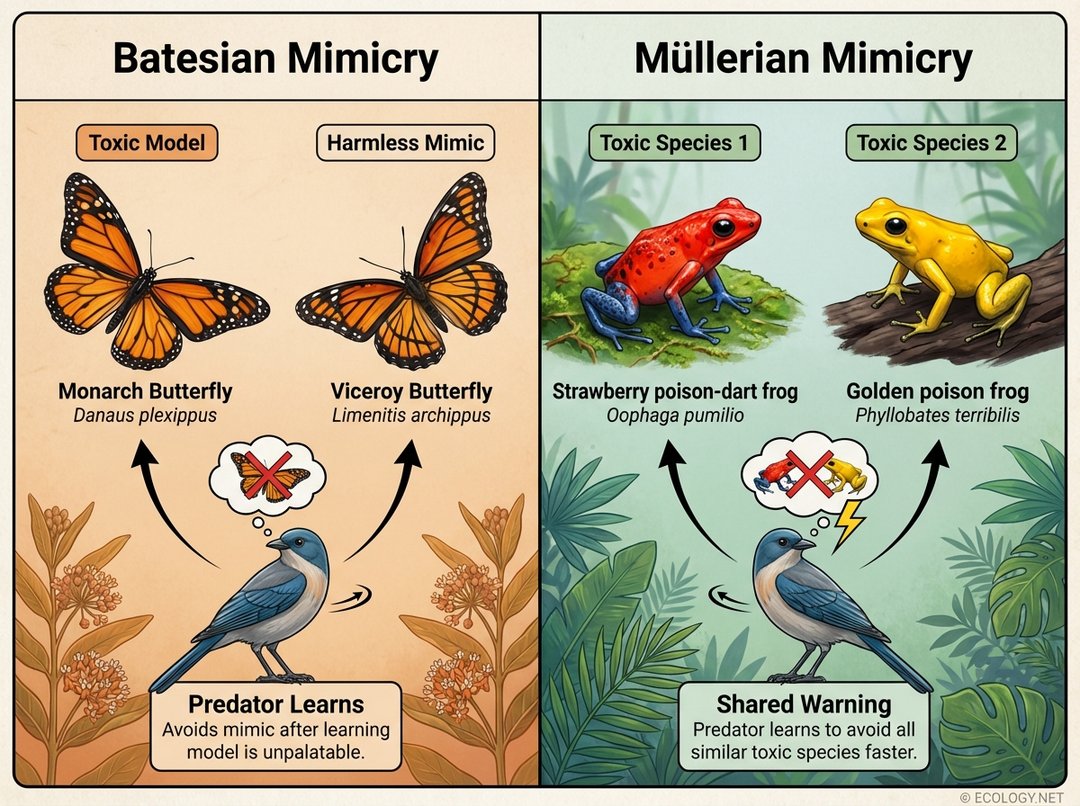

Batesian Mimicry

Named after the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, Batesian mimicry occurs when a harmless, palatable species evolves to imitate the warning signals of a dangerous, unpalatable species. The mimic gains protection from predators that have learned to avoid the genuine dangerous model.

- The Model: A truly toxic or dangerous species with a clear aposematic signal (e.g., a Monarch butterfly).

- The Mimic: A harmless species that looks very similar to the model (e.g., a Viceroy butterfly).

Predators, having learned to avoid the toxic model, will also avoid the harmless mimic, mistaking it for the dangerous species. This strategy is successful as long as the mimics are less numerous than the models, ensuring that predators primarily encounter the real danger and reinforce their avoidance behavior.

Müllerian Mimicry

Proposed by German naturalist Fritz Müller, Müllerian mimicry involves two or more different species, all of which are dangerous or unpalatable, evolving to share similar warning signals. This mutual resemblance benefits all species involved.

- Shared Signal: Multiple toxic or dangerous species develop similar warning colors or patterns (e.g., different species of poison dart frogs with similar bright coloration, or various stinging insects with black and yellow stripes).

When predators encounter any one of these species and experience a negative consequence, they learn to avoid all species that share that common warning signal. This effectively pools the learning experiences, meaning fewer individuals from each species need to be sacrificed for predators to learn the lesson. It is a powerful example of convergent evolution, where different species arrive at similar solutions to a shared problem.

The Evolutionary Arms Race Continues

Aposematism and mimicry are not static phenomena. They are part of a continuous evolutionary arms race between predators and prey. Predators may evolve resistance to toxins or develop strategies to circumvent defenses, while aposematic prey may refine their signals or enhance their toxicity. This dynamic interplay drives biodiversity and shapes ecological communities.

Understanding aposematism offers a profound insight into the intricate strategies life employs for survival. It highlights the power of communication in nature, where a splash of color can be a matter of life or death, a silent scream that echoes through the food web, ensuring the continuation of species.