Unveiling the Lake’s Hidden Layers: A Guide to Thermal Stratification

Lakes often appear as serene, uniform bodies of water, reflecting the sky and surrounding landscape. Yet, beneath their tranquil surfaces lies a complex, dynamic world shaped by an invisible force: temperature. This force orchestrates a remarkable phenomenon known as thermal stratification, where lakes develop distinct layers of water with different temperatures and densities. Understanding this layering is crucial, as it profoundly influences everything from the distribution of aquatic life to the cycling of vital nutrients.

Imagine diving into a lake on a warm summer day. You might feel the surface water pleasantly warm, but as you descend, a sudden chill envelops you. That abrupt temperature change marks the boundary of thermal stratification, a natural process that dictates the very pulse of a lake’s ecosystem.

What is Thermal Stratification? The Lake’s Three-Tiered System

Thermal stratification occurs when water bodies form stable layers due to differences in temperature and, consequently, density. Colder water is denser than warmer water, causing it to sink. This fundamental principle leads to the formation of three primary layers in a stratified lake during warmer months:

- The Epilimnion: The Warm, Upper Layer

This is the uppermost layer of the lake, directly exposed to sunlight and wind. It is the warmest and least dense layer, often well-mixed by wind action. Most photosynthetic activity occurs here, supporting a rich community of plankton and fish. - The Metalimnion (or Thermocline): The Transition Zone

Below the epilimnion lies the metalimnion, a transitional layer characterized by a rapid decrease in temperature with increasing depth. The most dramatic part of this zone, where the temperature gradient is steepest, is called the thermocline. This layer acts as a significant barrier, preventing the mixing of the water above and below it. - The Hypolimnion: The Cold, Deep Layer

The deepest and coldest layer of the lake is the hypolimnion. It is dense, dark, and typically remains at a consistently low temperature throughout the stratified period. Isolated from the surface, this layer receives little to no sunlight and is largely cut off from atmospheric oxygen.

These layers are not static; they are constantly interacting with their environment, yet their distinct properties remain largely intact during periods of stratification.

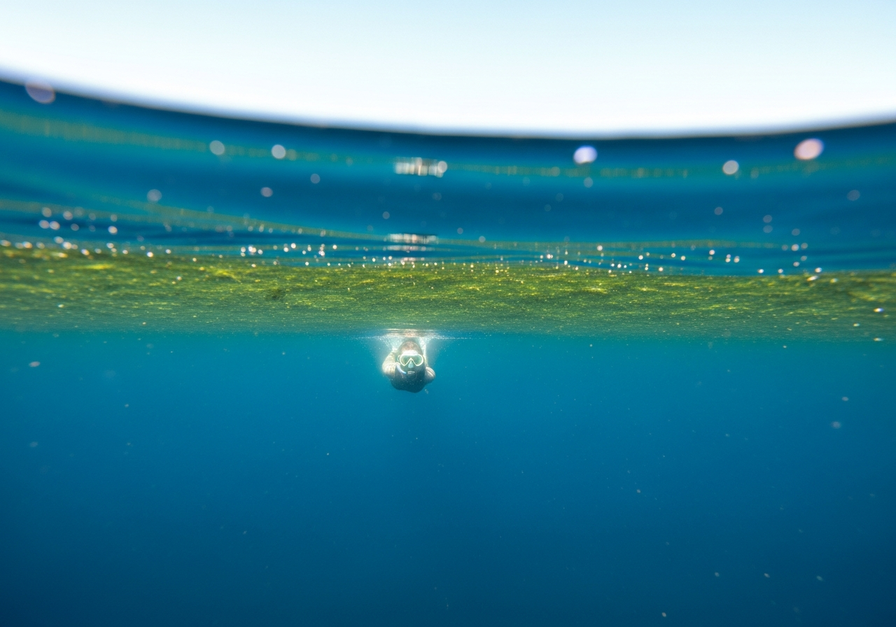

The image above beautifully captures the visible temperature gradient between the warm epilimnion and the cooler layer below, giving readers a concrete visual of how thermal stratification creates distinct layers in a lake.

The Thermocline: The Lake’s Invisible Barrier

The thermocline is arguably the most critical component of thermal stratification. It is not just a temperature boundary; it is a physical and chemical barrier that profoundly impacts the lake’s ecology. This sharp temperature gradient prevents the vertical mixing of water, effectively isolating the hypolimnion from the epilimnion.

Think of the thermocline as a ceiling for the deep water and a floor for the surface water. This separation has significant consequences:

- Oxygen Depletion: In the hypolimnion, decomposers consume oxygen as they break down organic matter that sinks from the epilimnion. Because the thermocline prevents oxygen from the surface from reaching these depths, the hypolimnion can become anoxic (devoid of oxygen), especially in productive lakes with high organic loads.

- Nutrient Trapping: Nutrients released from decaying organic matter in the hypolimnion become trapped below the thermocline. They cannot easily cycle back up to the sunlit epilimnion where they are needed for photosynthesis by algae and plants.

- Habitat Segregation: Aquatic organisms, from fish to invertebrates, must adapt to these distinct layers. Some species prefer the warm, oxygen-rich epilimnion, while others might seek the colder, darker hypolimnion, provided there is sufficient oxygen.

This underwater shot provides a direct visual of the thermocline, often invisible in surface images, by showing a natural plankton layer that marks the transition zone. This helps readers grasp the physical basis of the stratification layers.

Seasonal Turnover: The Lake’s Annual Reset

While stratification is a dominant feature during summer, it is not permanent. Lakes undergo dramatic changes with the seasons, leading to periods of mixing known as “turnover.” This annual reset is vital for the health of the entire ecosystem.

- Spring Turnover: As winter ice melts and spring temperatures rise, the surface water warms to approximately 4 degrees Celsius, the temperature at which water is densest. This warming causes the surface water to sink, while the slightly colder, deeper water rises. Wind action further aids this process, leading to a complete mixing of the lake from top to bottom. This mixing replenishes oxygen in the deep waters and brings trapped nutrients from the hypolimnion to the surface, fueling a burst of spring productivity.

- Summer Stratification: As summer progresses, the sun’s energy heats the surface water, making it less dense. The strong temperature gradient establishes the stable stratification described earlier, with the epilimnion, thermocline, and hypolimnion firmly in place.

- Fall Turnover: With the arrival of autumn, surface waters cool. As they cool, they become denser and sink, displacing the warmer, less dense water below. This process, combined with strong autumn winds, again leads to a complete mixing of the lake. Similar to spring turnover, fall turnover reoxygenates the deep waters and redistributes nutrients throughout the water column.

- Winter Stratification (Inverse Stratification): In colder climates, as surface water cools below 4 degrees Celsius and freezes, an inverse stratification can occur. The coldest water (0 degrees Celsius) is at the surface, under the ice, while the densest water (4 degrees Celsius) remains at the bottom. This creates a stable, albeit inverse, layering until spring.

This split-screen photograph illustrates the seasonal dynamics of thermal stratification, highlighting how the lake changes from a layered system in summer to a well-mixed state after spring turnover. This reinforces the article’s discussion of seasonal turnover events.

Why Does Stratification Matter? Ecological Impacts

The presence or absence of thermal stratification has profound ecological consequences, shaping the very fabric of a lake’s ecosystem:

- Nutrient Cycling: Turnover events are crucial for nutrient redistribution. Without them, nutrients would remain trapped in the hypolimnion, limiting productivity in the surface waters. Conversely, during stratification, the epilimnion can become nutrient-depleted, while the hypolimnion accumulates nutrients.

- Oxygen Availability: The hypolimnion’s isolation during stratification often leads to low oxygen levels, creating an inhospitable environment for many aquatic organisms. Fish and invertebrates that require high oxygen concentrations are forced to remain in the epilimnion or metalimnion.

- Algal Blooms: When fall turnover brings a sudden influx of nutrients to the surface after a long stratified period, it can sometimes trigger massive algal blooms, especially if nutrient pollution is present.

- Fish Distribution: Fish species have specific temperature and oxygen requirements. During stratification, cold-water fish like trout might be confined to a narrow band within the metalimnion or upper hypolimnion where temperatures are cool enough and oxygen is still sufficient. Warm-water fish, such as bass, thrive in the epilimnion.

- Chemical Processes: Anoxic conditions in the hypolimnion can lead to the release of phosphorus from sediments, further exacerbating nutrient problems. It can also lead to the formation of undesirable compounds like hydrogen sulfide.

Factors Influencing Stratification

Not all lakes stratify in the same way, or even at all. Several factors play a role:

- Depth: Deeper lakes are more likely to stratify strongly and for longer periods because their greater volume provides more thermal inertia and less susceptibility to complete mixing by wind. Shallow lakes, conversely, may mix frequently or remain unstratified.

- Size and Shape: Larger lakes with greater surface area are more exposed to wind, which can help mix the epilimnion but may not be strong enough to break down a deep thermocline. Lake shape can also influence wind fetch and mixing patterns.

- Climate: Regional climate dictates the duration and intensity of stratification. Lakes in tropical regions may stratify year-round (monomictic), while those in temperate zones experience distinct seasonal turnovers (dimictic). Polar lakes may remain inversely stratified or unstratified for much of the year.

- Wind Exposure: Strong, consistent winds can increase the depth of the epilimnion by mixing more of the surface water, potentially weakening the thermocline.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts and Implications

For those delving deeper into limnology, the nuances of thermal stratification extend further:

- Lake Classification by Mixing Regimes:

- Monomictic Lakes: Mix once a year. Cold monomictic lakes mix in summer and are inversely stratified in winter (e.g., some deep arctic lakes). Warm monomictic lakes mix in winter and stratify in summer (e.g., many subtropical lakes).

- Dimictic Lakes: Mix twice a year, typically in spring and fall (e.g., most temperate lakes).

- Polymictic Lakes: Mix frequently or continuously throughout the year, often shallow lakes exposed to wind.

- Amictic Lakes: Never mix, permanently ice-covered (e.g., some Antarctic lakes).

- Oligomictic Lakes: Stratify and mix only irregularly, often in tropical regions with stable warm temperatures.

- Internal Seiches: The thermocline itself can oscillate like a giant underwater wave, known as an internal seiche. These movements can temporarily bring hypolimnetic water closer to the surface or cause localized mixing.

- Human Impacts:

- Eutrophication: Increased nutrient loading from human activities (agriculture, wastewater) can intensify stratification. More organic matter sinks to the hypolimnion, leading to more severe oxygen depletion and potentially larger releases of internal phosphorus during anoxic conditions.

- Climate Change: Rising air temperatures are leading to warmer surface waters and longer periods of stratification in many lakes. This can result in earlier onset of stratification, later breakdown, and stronger, shallower thermoclines, exacerbating oxygen depletion in the hypolimnion and altering nutrient cycling.

- Management Implications: Understanding stratification is vital for lake management. Strategies for managing water quality, fisheries, and even drinking water reservoirs must account for the layered nature of lakes. For example, artificial destratification (using aerators to mix the water) is sometimes employed to improve oxygen conditions in the hypolimnion, though it can have other ecological trade-offs.

The Dynamic Heart of Our Lakes

Thermal stratification is far more than just a temperature difference; it is the dynamic heart of a lake’s ecosystem, dictating its chemistry, biology, and overall health. From the gentle ripples on the surface to the dark, cold depths, every layer plays a crucial role in the intricate web of aquatic life. By appreciating these hidden layers and their seasonal dance, we gain a deeper understanding of these vital freshwater resources and the importance of protecting their delicate balance.