Beneath our feet lies a hidden world, a complex tapestry of life and geology that often goes unnoticed. This subterranean realm, far from being uniform, is a meticulously layered archive of environmental history and ecological processes. Understanding this layered structure, known as a soil profile, is fundamental to comprehending everything from agricultural productivity to the health of entire ecosystems.

Imagine slicing vertically through the earth, much like cutting into a multi-layered cake. What you would reveal is a distinct arrangement of horizontal layers, each with unique characteristics. These layers are called soil horizons, and together they tell a profound story about the soil’s formation, its composition, and the forces that have shaped it over millennia.

What is a Soil Profile? Unveiling the Earth’s Layers

A soil profile is essentially a vertical cross-section of the soil, extending from the surface down to the unweathered parent material. It is a visual representation of the different horizons that have developed over time due to various physical, chemical, and biological processes. Each horizon represents a stage in the soil’s development, reflecting the movement of water, minerals, and organic matter through the soil column.

Ecologists, farmers, and soil scientists study soil profiles to gain insights into soil fertility, water retention, nutrient cycling, and the suitability of land for different uses. It is a diagnostic tool that reveals the very essence of the ground we stand upon.

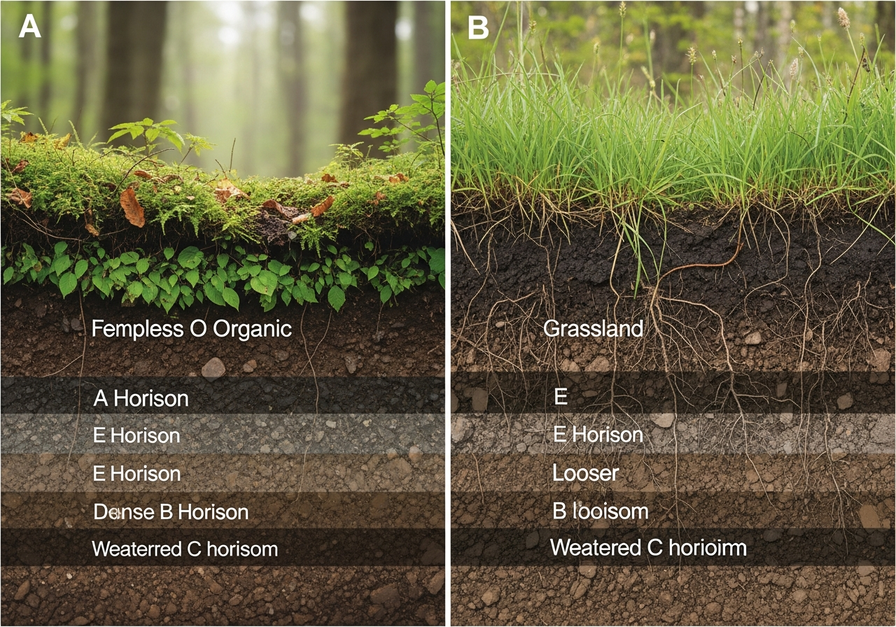

This image provides a tangible, real-world illustration of the layered horizons described in the article, making the concept of a soil profile visually accessible.

The ABCs of Soil Horizons: A Closer Look at Each Layer

While the number and thickness of horizons can vary greatly, a generalized soil profile typically includes several key layers. These are often designated by letters, making them easier to identify and discuss.

O Horizon: The Organic Blanket

- Description: This is the uppermost layer, primarily composed of organic materials at various stages of decomposition. It is often dark in color.

- Composition: Freshly fallen leaves, twigs, moss, and other plant debris (Oi sub-horizon), partially decomposed organic matter (Oe sub-horizon), and highly decomposed humus (Oa sub-horizon).

- Role: Protects the soil surface, reduces erosion, retains moisture, and provides a rich source of nutrients as it decomposes. It is teeming with microbial life.

- Examples: The thick layer of pine needles in a conifer forest or the leaf litter on a deciduous forest floor.

A Horizon: The Topsoil, Where Life Flourishes

- Description: Often referred to as topsoil, this layer is typically dark and rich, lying directly beneath the O horizon (or at the surface if O is absent).

- Composition: A mixture of decomposed organic matter (humus) and mineral particles (sand, silt, clay). It is characterized by significant biological activity, including roots, earthworms, and microorganisms.

- Role: The most fertile layer, crucial for plant growth due to its high nutrient content and good water retention. It is where most biological activity occurs.

- Examples: The dark, crumbly soil found in a healthy garden bed or the rich upper layer of a prairie grassland.

E Horizon: The Leaching Layer

- Description: Not always present, this horizon is typically lighter in color than the A horizon and is found beneath it.

- Composition: Characterized by the loss of clay, iron, aluminum, and organic matter due to leaching (eluviation) by downward-moving water. This leaves behind a higher concentration of resistant minerals like quartz, giving it a bleached appearance.

- Role: A zone of significant mineral removal.

- Examples: Often prominent in older forest soils, particularly those in humid climates where water readily percolates through the soil.

B Horizon: The Subsoil, Where Accumulation Occurs

- Description: Known as the subsoil, this layer is usually denser and often exhibits distinct colors, such as reddish-brown or yellowish-brown.

- Composition: A zone of accumulation (illuviation) where materials leached from the A and E horizons are deposited. This can include clay, iron oxides, aluminum oxides, and humus. It may also contain carbonates in drier climates.

- Role: Stores water and nutrients, though it is generally less fertile and has less organic matter than the A horizon. Its density can affect root penetration.

- Examples: The reddish clay layer often seen beneath the topsoil in many agricultural fields or the dense, iron-rich layer in a forest soil.

C Horizon: The Parent Material

- Description: This layer consists of partially weathered parent material, which is the geological material from which the soil formed.

- Composition: Unconsolidated material that has undergone minimal soil-forming processes. It can be bedrock, glacial till, river sediments, or wind-blown deposits.

- Role: Provides the raw material for soil formation. Its composition significantly influences the texture, mineralogy, and chemical properties of the overlying horizons.

- Examples: A layer of fractured shale, unconsolidated sand, or glacial gravel beneath the developed soil layers.

R Horizon: The Bedrock

- Description: The deepest layer, consisting of unweathered, consolidated bedrock.

- Composition: Solid rock, such as granite, sandstone, or limestone.

- Role: The ultimate source of the parent material for the C horizon and, eventually, the entire soil profile.

Factors Shaping the Soil Story: The CLORPT Equation

The unique characteristics of any soil profile are the result of a complex interplay of five major soil-forming factors, often remembered by the acronym CLORPT:

- Climate: Temperature and precipitation are paramount.

- Impact: High rainfall leads to more leaching, potentially forming distinct E horizons and moving nutrients deeper. Warm, humid climates accelerate weathering and decomposition. Cold, dry climates slow down these processes, often resulting in shallower profiles with less organic matter.

- Example: Tropical rainforests have deep, highly weathered soils with rapid nutrient cycling, while arctic tundras have shallow, often frozen soils with slow decomposition.

- Organisms: Plants, animals, and microorganisms are vital engineers of the soil.

- Impact: Plant roots break up soil, add organic matter, and extract nutrients. Microbes decompose organic matter, cycle nutrients, and form soil aggregates. Earthworms and burrowing animals mix soil layers, create pores, and enhance aeration.

- Example: Grasslands, with their dense fibrous root systems, develop thick, dark A horizons rich in organic matter. Forests, with their leaf litter, often have a prominent O horizon.

- Relief (Topography): The shape of the land surface influences water movement and erosion.

- Impact: Steep slopes experience more erosion and shallower soils, while flatter areas accumulate more soil and organic matter. Depressions can collect water, leading to waterlogged soils.

- Example: Soils on hilltops are often thinner and drier than those in valleys, which tend to be deeper and moister.

- Parent Material: The geological starting material from which the soil develops.

- Impact: The type of rock or sediment determines the initial mineral composition, texture, and chemical properties of the soil. For instance, soils derived from limestone will be rich in calcium, while those from granite will be more acidic.

- Example: Soils formed from volcanic ash are typically very fertile, while those from pure quartz sand are often nutrient-poor.

- Time: Soil formation is a continuous, gradual process.

- Impact: Young soils have less developed horizons, resembling their parent material more closely. Over long periods, horizons become more distinct, and the soil develops unique characteristics reflecting the cumulative effects of climate, organisms, and relief.

- Example: A recently exposed glacial till will have a very young soil profile, while an ancient floodplain might exhibit highly developed, deep horizons.

By visually comparing two distinct ecosystems, this illustration reinforces the article’s discussion of how climate, organisms, and parent material shape soil profiles.

Diversity Beneath Our Feet: Examples of Soil Profiles Across Ecosystems

The CLORPT factors combine in countless ways to create an astonishing diversity of soil profiles around the globe. Here are a few examples:

Forest Soils (e.g., Spodosols, Alfisols)

- Characteristics: Often feature a prominent O horizon from leaf litter. Many forest soils in humid, temperate regions develop a distinct E horizon due to leaching, followed by a reddish or brownish B horizon where iron and aluminum accumulate.

- Key Influences: Abundant organic matter from trees, significant rainfall promoting leaching, and often acidic conditions.

Grassland Soils (e.g., Mollisols)

- Characteristics: Renowned for their thick, dark A horizons, rich in organic matter from the decomposition of dense grass root systems. The B horizon is often less distinct than in forest soils, and calcium carbonate accumulation can be common in drier grasslands.

- Key Influences: Extensive root systems of grasses, moderate rainfall, and often fire, which returns nutrients to the soil surface.

Desert Soils (e.g., Aridisols)

- Characteristics: Typically shallow, sandy, and low in organic matter due to sparse vegetation and limited moisture. Horizons are often weakly developed. They frequently exhibit accumulations of salts, gypsum, or calcium carbonate (caliche) in the B or C horizons due to evaporation.

- Key Influences: Extreme aridity, minimal vegetation, and slow weathering processes.

This image visually represents the article’s point about desert soils being shallow, sandy, and low in organic matter, helping readers grasp the contrast with richer soils.

Wetland Soils (e.g., Histosols)

- Characteristics: Dominated by very thick organic horizons (O horizons) that can extend for meters. These soils form in waterlogged conditions where decomposition is slowed due to a lack of oxygen, leading to the accumulation of peat.

- Key Influences: Persistent saturation with water, which creates anaerobic conditions and inhibits microbial decomposition.

Why Does It Matter? Practical Insights from Soil Profiles

Understanding soil profiles is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound practical implications across various fields:

- Agriculture and Food Production: Farmers rely on soil profiles to assess fertility, drainage, and suitability for specific crops. A deep, rich A horizon is a farmer’s best friend.

- Forestry and Ecosystem Health: Foresters use soil profiles to determine tree species suitability, predict growth rates, and manage forest health. The presence of certain horizons can indicate past disturbances or nutrient limitations.

- Construction and Engineering: Engineers examine soil profiles to evaluate bearing capacity, stability, and drainage for foundations, roads, and other infrastructure projects. The density and composition of B and C horizons are critical.

- Environmental Management: Soil profiles are crucial for understanding water filtration, pollutant movement, and carbon sequestration. They help in designing effective waste disposal sites and managing contaminated land.

- Archaeology: Archaeologists study soil profiles to understand past landscapes, human activities, and the preservation of artifacts. Distinct layers can reveal ancient settlements or environmental changes.

The Enduring Story Beneath Our Feet

The soil profile is far more than just dirt; it is a dynamic, living system, a historical record, and a vital resource. Each horizon tells a part of the story, from the fresh organic matter at the surface to the ancient parent material below. By learning to read these layers, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate processes that sustain life on Earth and the critical importance of protecting this invaluable natural heritage.

The next time you walk across a field or through a forest, take a moment to consider the incredible world beneath your feet. It is a world of constant change, silent growth, and enduring history, all encapsulated within the remarkable structure of the soil profile.