Imagine a world where trees are a rarity, where the ground beneath your feet is perpetually frozen, and where life thrives against incredible odds. Welcome to the tundra biome, a landscape of breathtaking beauty and profound resilience. Often misunderstood, this unique ecosystem plays a critical role in our planet’s health, harboring specialized life forms and influencing global climate patterns. Join us on a journey to explore the wonders of the tundra, from its icy foundations to the vibrant life that calls it home.

Unveiling the Tundra Biome: Earth’s Coldest Frontier

The tundra biome is characterized by its extremely cold temperatures, low precipitation, short growing seasons, and a distinctive treeless landscape. The word “tundra” itself comes from the Finnish word tunturia, meaning “treeless plain.” This harsh environment is found in the Earth’s polar regions and at high altitudes, where conditions prevent the growth of tall trees.

Key characteristics that define the tundra include:

- Permafrost: A layer of permanently frozen ground that lies beneath the surface, preventing deep root growth and water drainage.

- Low Temperatures: Average annual temperatures are well below freezing, with short, cool summers.

- Low Precipitation: Despite the ice and snow, the tundra is often considered a cold desert, receiving minimal rainfall or snowfall.

- Short Growing Season: Plants must complete their entire life cycle within a few weeks or months during the brief summer.

- Low Biodiversity: While species numbers are lower than in warmer biomes, the organisms present are highly specialized and adapted.

Two Faces of the Tundra: Arctic and Alpine

While sharing many similarities, the tundra biome is broadly divided into two main types, each with its own unique geographic and ecological nuances.

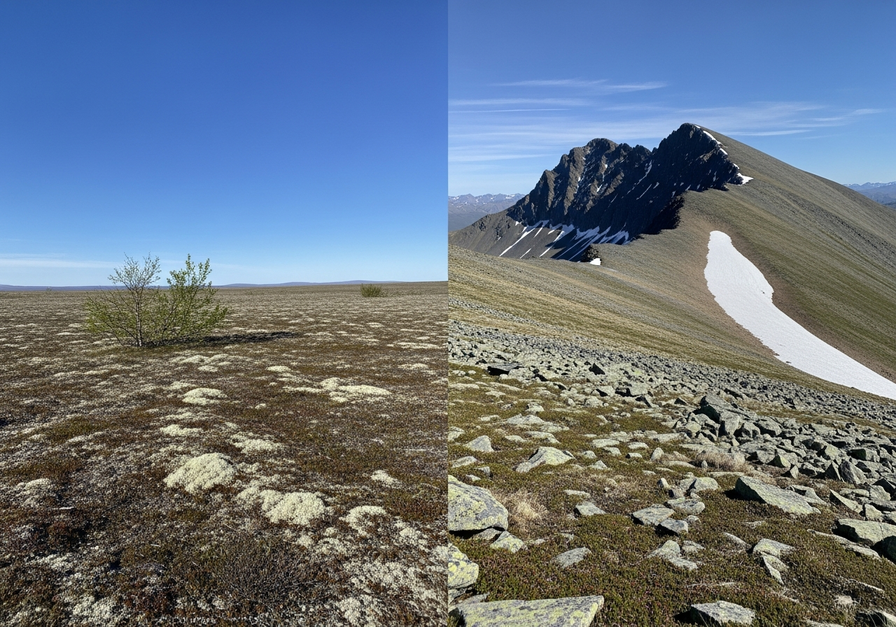

This image highlights the distinct types of tundra—Arctic and Alpine—providing a visual contrast that complements the article’s explanation of biome variations.

The Arctic Tundra: A Vast Northern Expanse

The Arctic tundra encircles the North Pole, stretching across northern North America, Europe, and Asia. It is the largest of the two tundra types and is defined by its continuous permafrost layer. This frozen ground creates a landscape of shallow lakes, bogs, and marshes during the summer thaw, as water cannot drain downwards. The vegetation here consists primarily of mosses, lichens, sedges, grasses, and dwarf shrubs like willows and birches, all hugging the ground to escape the biting winds and conserve warmth.

- Location: High latitudes, encircling the Arctic Ocean.

- Permafrost: Present and extensive, shaping the landscape.

- Vegetation: Dominated by low-lying plants, adapted to cold and wind.

- Wildlife: Home to iconic species such as polar bears, caribou, arctic foxes, and lemmings.

The Alpine Tundra: Mountains Above the Treeline

Alpine tundra occurs at high altitudes on mountains worldwide, above the treeline where trees cannot grow due to cold temperatures and strong winds. Unlike the Arctic tundra, alpine tundra does not typically have permafrost, though the ground can freeze solid seasonally. Its landscape is often rockier, with thinner soils and better drainage. The plants here are similar to those in the Arctic tundra, featuring cushion plants, grasses, and small flowering plants that can withstand harsh conditions.

- Location: High elevations on mountain ranges globally, such as the Rockies, Andes, Himalayas.

- Permafrost: Generally absent, though seasonal freezing occurs.

- Vegetation: Hardy, low-growing plants adapted to rocky terrain and intense UV radiation.

- Wildlife: Includes mountain goats, bighorn sheep, marmots, and pikas, often distinct from Arctic species.

Life’s Ingenuity: Adaptations to the Tundra’s Extremes

Survival in the tundra demands extraordinary adaptations. Both plants and animals have evolved remarkable strategies to cope with the cold, wind, and limited resources.

This image shows animal and plant adaptations to the harsh Arctic environment, reinforcing the sections on biodiversity, resilience, and the life-supporting nature of the tundra.

Plant Power: Surviving the Short Summer

Tundra plants are masters of efficiency, making the most of the brief growing season.

- Low Growth Form: Most plants grow close to the ground, forming mats or cushions. This protects them from strong winds and allows them to absorb heat from the sun-warmed soil. Examples include arctic poppies and moss campion.

- Rapid Growth and Reproduction: Many plants have short life cycles, flowering and producing seeds quickly during the summer. Some reproduce asexually through runners or budding.

- Dark Pigmentation: Some plants have dark leaves or stems to absorb more solar radiation, helping them warm up faster.

- Hairy Stems and Leaves: A fuzzy coating can trap a layer of warm air, insulating the plant.

- Perennial Nature: Most tundra plants are perennials, meaning they live for several years, avoiding the need to re-establish from seed each season.

Animal Resilience: Thriving in the Cold

Tundra animals employ a variety of tactics to endure the long, frigid winters and capitalize on the short, abundant summers.

- Insulation: Many animals possess thick layers of fur or feathers, often changing color seasonally. The arctic fox, for instance, sports a dense white coat in winter and a brown one in summer. Polar bears have two layers of fur and a thick layer of blubber.

- Hibernation or Torpor: Some smaller mammals, like marmots and ground squirrels, hibernate through the winter, slowing their metabolism to conserve energy.

- Migration: Large herbivores, such as caribou and reindeer, undertake epic migrations to find food and escape the harshest winter conditions.

- Specialized Diets: Animals like lemmings and voles burrow under the snow to find vegetation, while predators like the snowy owl have keen senses to hunt prey even under snow cover.

- Compact Body Shapes: Many tundra animals have smaller ears, tails, and limbs compared to their temperate relatives. This reduces the surface area exposed to the cold, minimizing heat loss.

The Permafrost: A Frozen Foundation Under Threat

Perhaps the most defining feature of the Arctic tundra is permafrost, ground that remains completely frozen for at least two consecutive years. This frozen layer can extend hundreds of meters deep and holds vast quantities of ancient organic matter.

This image illustrates permafrost thaw and thermokarst lakes, visually reinforcing the article’s discussion of climate change impacts on the tundra ecosystem.

The Role of Permafrost in the Ecosystem

Permafrost acts as a barrier, preventing water from draining downwards, which leads to the formation of numerous shallow lakes, ponds, and wetlands during the summer thaw. It also supports the unique low-lying vegetation by keeping roots near the surface where nutrients are available. Crucially, permafrost stores an immense amount of carbon, locked away in frozen plant and animal remains accumulated over millennia.

The Alarming Reality of Permafrost Thaw

Climate change is causing the Arctic to warm at an accelerated rate, leading to widespread permafrost thaw. This has profound implications:

- Thermokarst Lakes: As ice-rich permafrost thaws, the ground collapses, creating depressions that fill with water, forming thermokarst lakes. These lakes drastically alter the landscape and local hydrology.

- Greenhouse Gas Release: The thawing permafrost releases ancient organic matter, which then decomposes. This decomposition releases significant amounts of potent greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide and methane, into the atmosphere. This creates a dangerous feedback loop, where warming causes more thawing, which causes more warming.

- Infrastructure Damage: Thawing permafrost destabilizes the ground, threatening roads, buildings, pipelines, and other infrastructure built on it.

- Changes in Hydrology: Altered drainage patterns can lead to drier uplands and wetter lowlands, impacting plant communities and wildlife habitats.

The Tundra’s Vital Ecosystem Services

Beyond its unique biology, the tundra provides invaluable services to the planet.

- Carbon Storage: The permafrost acts as a massive carbon sink, holding an estimated 1,700 billion metric tons of carbon, roughly twice the amount currently in the atmosphere. Protecting this frozen carbon is critical for mitigating climate change.

- Biodiversity Hotspot: Despite its harshness, the tundra supports a specialized array of flora and fauna, many of which are found nowhere else. These species contribute to global biodiversity and ecological resilience.

- Regulation of Global Climate: The vast, reflective snow and ice cover of the Arctic tundra plays a role in regulating Earth’s temperature by reflecting solar radiation back into space.

Threats and Conservation: Protecting a Fragile World

The tundra biome is one of the most vulnerable ecosystems on Earth, facing a multitude of threats.

- Climate Change: As discussed, warming temperatures are the primary driver of permafrost thaw, leading to habitat loss, changes in species distribution, and the release of greenhouse gases.

- Resource Extraction: The tundra sits atop significant reserves of oil, natural gas, and minerals. Extraction activities can cause habitat destruction, pollution, and disturbance to wildlife.

- Pollution: Atmospheric pollutants, including persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and heavy metals, can travel long distances and accumulate in the tundra food web, impacting top predators.

- Human Disturbance: Increased human presence, tourism, and infrastructure development can fragment habitats and stress sensitive species.

Conservation efforts are crucial to safeguard the tundra. These include establishing protected areas, implementing sustainable resource management practices, reducing global greenhouse gas emissions, and supporting scientific research to better understand and monitor this rapidly changing biome. International cooperation is vital, as the tundra spans multiple countries and its health impacts the entire globe.

Embracing the Tundra’s Enduring Spirit

The tundra biome, with its stark beauty and incredible resilience, offers a powerful lesson in adaptation and survival. From the low-lying lichens clinging to frozen ground to the majestic caribou traversing vast plains, life here finds a way to flourish against formidable odds. Understanding the tundra is not just about appreciating a distant, cold landscape; it is about recognizing its profound connection to our global climate and the intricate web of life on Earth. As we face the challenges of a changing planet, the tundra stands as a vital indicator of environmental health and a testament to nature’s enduring spirit, urging us to protect its fragile balance for generations to come.