Unmasking Phenotypic Plasticity: Nature’s Master of Adaptation

Imagine a single organism, born with a specific genetic blueprint, yet capable of transforming its very appearance, behavior, or physiology to thrive in wildly different surroundings. This remarkable ability is not science fiction, but a fundamental biological phenomenon known as phenotypic plasticity. It is nature’s ingenious way of allowing life to adapt on the fly, without waiting for generations of evolutionary change.

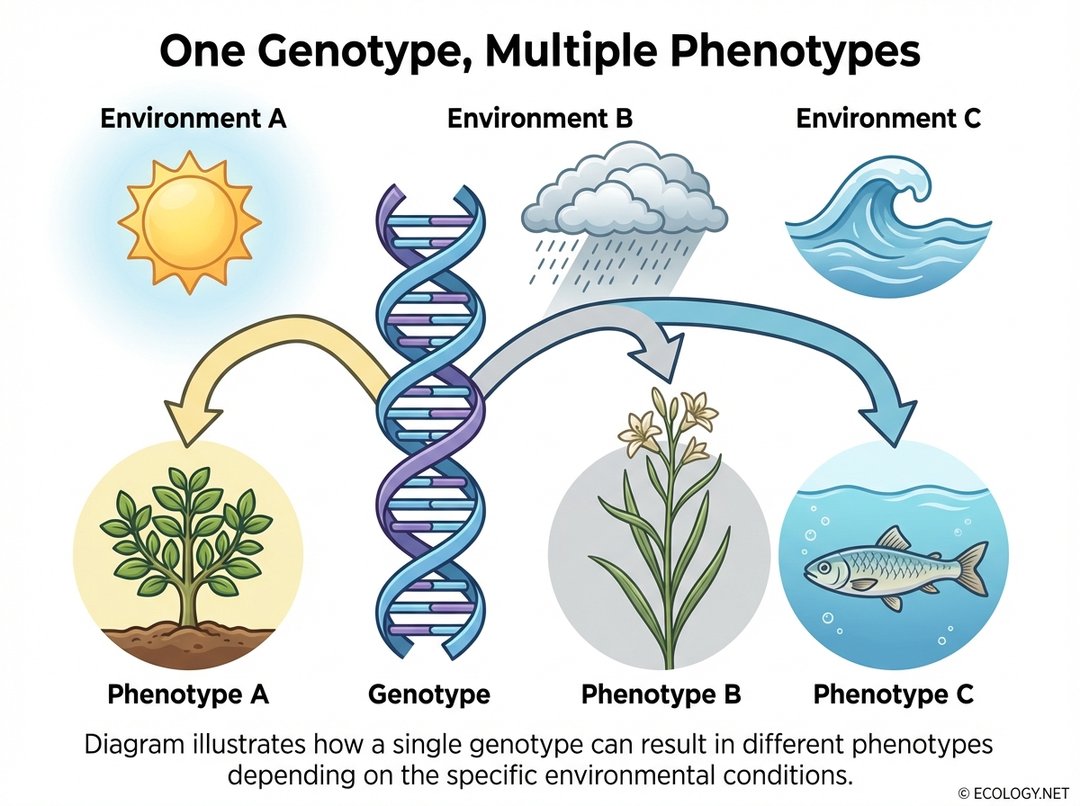

At its core, phenotypic plasticity is the capacity of a single genotype to produce multiple phenotypes when exposed to different environmental conditions. Think of it as an organism having a versatile toolkit, where the tools it uses, and how it uses them, depend entirely on the challenges and opportunities presented by its surroundings. This dynamic interplay between genes and environment is crucial for survival across diverse and changing landscapes.

Genotype, Phenotype, and Environment: The Core Trio

To fully grasp phenotypic plasticity, it is essential to understand three key terms:

- Genotype: This refers to the complete set of genetic material an organism inherits. It is the underlying blueprint, the DNA sequence that dictates potential traits.

- Phenotype: This is the observable expression of the genotype. It encompasses all of an organism’s characteristics, including its physical appearance, physiological processes, and even behavior. A phenotype is what we actually see and measure.

- Environment: This includes all external factors that influence an organism’s life. It can be anything from temperature, light availability, nutrient levels, and water salinity to the presence of predators or competitors.

Phenotypic plasticity highlights that the phenotype is not solely determined by the genotype. Instead, it is a product of the genotype’s interaction with the environment. A single genotype can give rise to a variety of phenotypes, each optimized for a particular set of environmental circumstances.

Why is Phenotypic Plasticity So Important?

This ability to change is not just a biological curiosity; it is a powerful evolutionary advantage. In a world where conditions are rarely constant, plasticity offers organisms a lifeline.

- Enhanced Survival: Organisms can adjust to fluctuating resources, temperatures, or predator pressures, increasing their chances of survival in unpredictable habitats.

- Broader Distribution: Species with high plasticity can often colonize and thrive in a wider range of environments than those with fixed phenotypes.

- Rapid Response: Unlike genetic evolution, which takes many generations, phenotypic plasticity allows for immediate, individual-level responses to environmental shifts.

- Reduced Competition: By altering their traits, individuals might exploit different resources or niches, reducing competition with others in their population.

Everyday Wonders: Examples of Phenotypic Plasticity in Action

The natural world is brimming with examples of phenotypic plasticity, showcasing its incredible diversity and impact across all forms of life.

Plants: Masters of Morphological Adaptation

Plants, rooted in place, cannot simply move away from unfavorable conditions. Their survival often hinges on their ability to alter their growth and structure.

- Light Availability: As seen in the image, a plant grown in full sun might be short and bushy with thick, small leaves to minimize water loss and maximize light absorption efficiency. The exact same plant grown in shade, however, might become tall and spindly with large, thin leaves to reach for scarce light and capture as much as possible.

- Nutrient Levels: When nutrients are scarce, some plants develop extensive root systems to forage more effectively. In nutrient-rich soil, they might invest more energy into shoot growth and reproduction.

- Water Availability: Desert plants can exhibit remarkable plasticity. In response to drought, they might shed leaves, reduce stomatal opening, or even alter their photosynthetic pathways to conserve water.

Animals: From Body Shape to Behavior

Animals also display a wide array of plastic responses, often involving more complex physiological and behavioral changes.

- Tadpoles and Predators: Some tadpole species develop larger tails and deeper bodies when they detect chemical cues from predators in their water. This altered morphology makes them harder for predators to catch.

- Water Fleas (Daphnia): These tiny crustaceans can grow protective helmets and spines when exposed to predators, making them less palatable or harder to consume.

- Locusts: The desert locust provides a classic example. When populations are sparse, they are solitary, camouflaged, and avoid each other. However, when population density increases, they transform into gregarious, brightly colored, swarming insects capable of devastating agricultural fields. This change is triggered by tactile stimulation from other locusts.

- Fish and Water Flow: Fish living in fast-flowing rivers often develop more streamlined bodies and larger fins compared to their counterparts in calm waters, allowing them to navigate strong currents more efficiently.

- Dietary Shifts: Some bird species can alter the size and shape of their beaks over their lifetime in response to changes in available food sources, allowing them to exploit different types of seeds or insects.

Microorganisms: Rapid Responses to Microenvironments

Even single-celled organisms exhibit plasticity. Bacteria can alter their metabolic pathways, cell wall composition, or even form biofilms in response to nutrient availability, pH changes, or the presence of antibiotics. This rapid adaptability is a major challenge in medicine.

Delving Deeper: Quantifying Plasticity with Reaction Norms

While examples illustrate the concept, scientists need ways to quantify and compare phenotypic plasticity across different genotypes and species. This is where the concept of a “reaction norm” becomes invaluable.

What is a Reaction Norm?

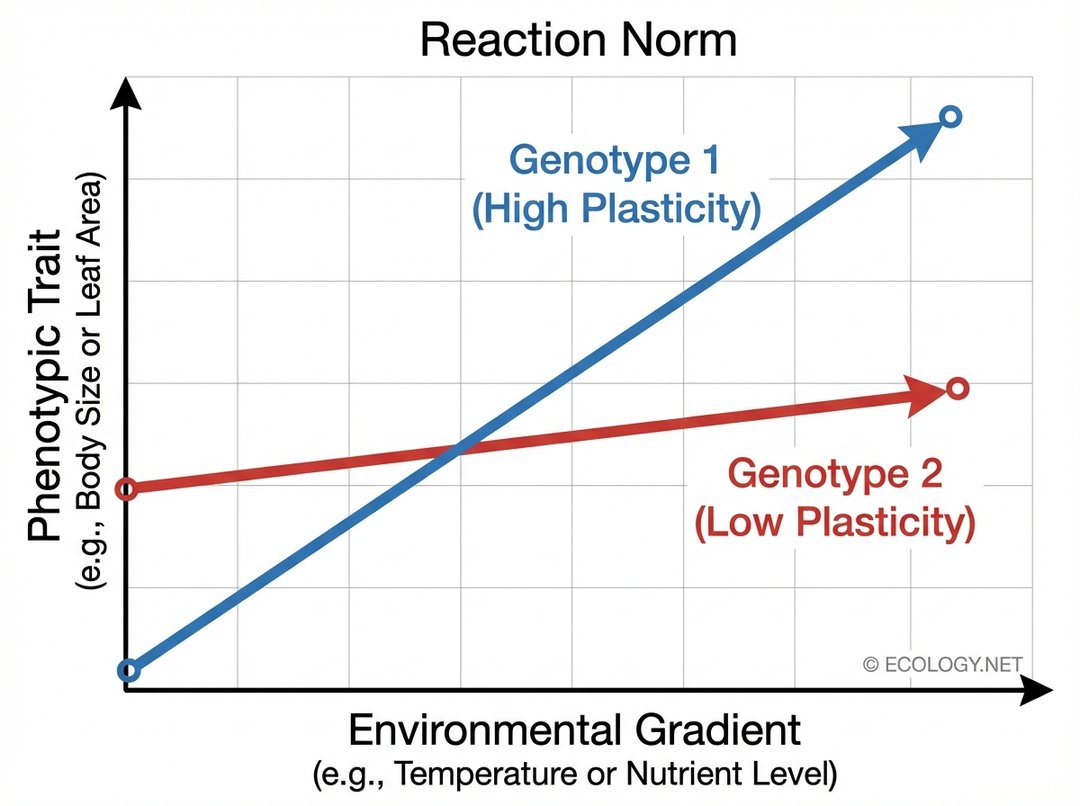

A reaction norm is essentially a graphical representation of how a single genotype’s phenotype changes across a range of environmental conditions. It plots the value of a phenotypic trait (e.g., body size, leaf area, growth rate) on the Y-axis against an environmental gradient (e.g., temperature, nutrient concentration, light intensity) on the X-axis.

Each line on such a graph represents the reaction norm for a specific genotype. By comparing the slopes and shapes of these lines, ecologists and evolutionary biologists can gain profound insights:

- Steep Slope: A steep slope indicates high phenotypic plasticity. The genotype shows a significant change in its phenotype in response to environmental variation.

- Flat Slope: A flat slope suggests low phenotypic plasticity. The genotype’s phenotype remains relatively stable despite environmental changes.

- Different Slopes: If different genotypes have different slopes, it means they vary in their degree of plasticity. Some genotypes are more plastic than others.

- Crossing Reaction Norms: When reaction norms cross, it signifies a “genotype by environment interaction.” This means that the optimal phenotype for one environment might be produced by one genotype, while a different genotype produces the optimal phenotype in another environment. This is a powerful indicator of how selection can act differently on genotypes depending on the specific environmental context.

Reaction norms are powerful tools for understanding the genetic basis of plasticity, predicting how populations might respond to environmental change, and even for selective breeding in agriculture.

The Trade-offs: Costs and Limits of Plasticity

While highly beneficial, phenotypic plasticity is not without its costs or limitations. Organisms cannot be infinitely plastic.

- Energetic Costs: Developing and maintaining the machinery for sensing the environment and altering phenotypes can be energetically expensive.

- Information Costs: Accurately sensing the environment and making the “right” phenotypic adjustment requires reliable cues. Misinterpreting cues can lead to maladaptive phenotypes.

- Developmental Constraints: There are often limits to how much a phenotype can change. A plant cannot suddenly become an animal, nor can a fish grow lungs.

- Lag Time: Some plastic responses are not instantaneous. There can be a delay between environmental change and phenotypic adjustment, which can be critical in rapidly changing conditions.

- Reduced Specialization: Highly plastic organisms might be generalists, potentially sacrificing peak performance in any single environment for the ability to survive across many.

Plasticity in a Changing World: A Glimmer of Hope?

In an era of rapid global environmental change, understanding phenotypic plasticity has become more critical than ever. As climates shift, habitats fragment, and new pressures emerge, the ability of species to adjust their phenotypes quickly could be a key factor in their survival.

Plasticity might offer a buffer, allowing populations to persist in altered environments long enough for genetic evolution to catch up, or even to prevent extinction in some cases. However, the limits of plasticity mean that not all species will be able to cope. Identifying which species possess high plasticity and understanding the mechanisms behind it is a vital area of research for conservation efforts.

The Unseen Power of Adaptation

Phenotypic plasticity is a testament to the incredible adaptability of life on Earth. It is a silent, continuous dance between an organism’s genetic potential and the ever-changing world around it. From the subtle shift in a plant’s leaf shape to the dramatic transformation of a locust, plasticity allows life to persist, thrive, and continually surprise us with its resilience. By appreciating this fundamental concept, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricate web of interactions that shape biodiversity and the future of our planet.