The Unseen Architects: How Fertilizers Shape Our World

From the vibrant hues of a blossoming garden to the vast fields feeding billions, plants are the silent powerhouses of our planet. Yet, their tireless work relies on a delicate balance of nutrients, many of which are not always readily available in sufficient quantities. This is where fertilizers step in, acting as the unseen architects that bolster plant growth, enhance yields, and ultimately, sustain life on Earth. But what exactly are these compounds, and how do they wield such profound influence?

What Are Fertilizers and Why Do Plants Need Them?

At its core, a fertilizer is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or plant tissues to supply one or more plant nutrients essential for the growth of plants. Think of them as a carefully formulated meal for plants, providing the vital building blocks they need to thrive. Just like humans require a balanced diet of proteins, carbohydrates, and vitamins, plants demand specific elements to perform their biological functions, from photosynthesis to root development.

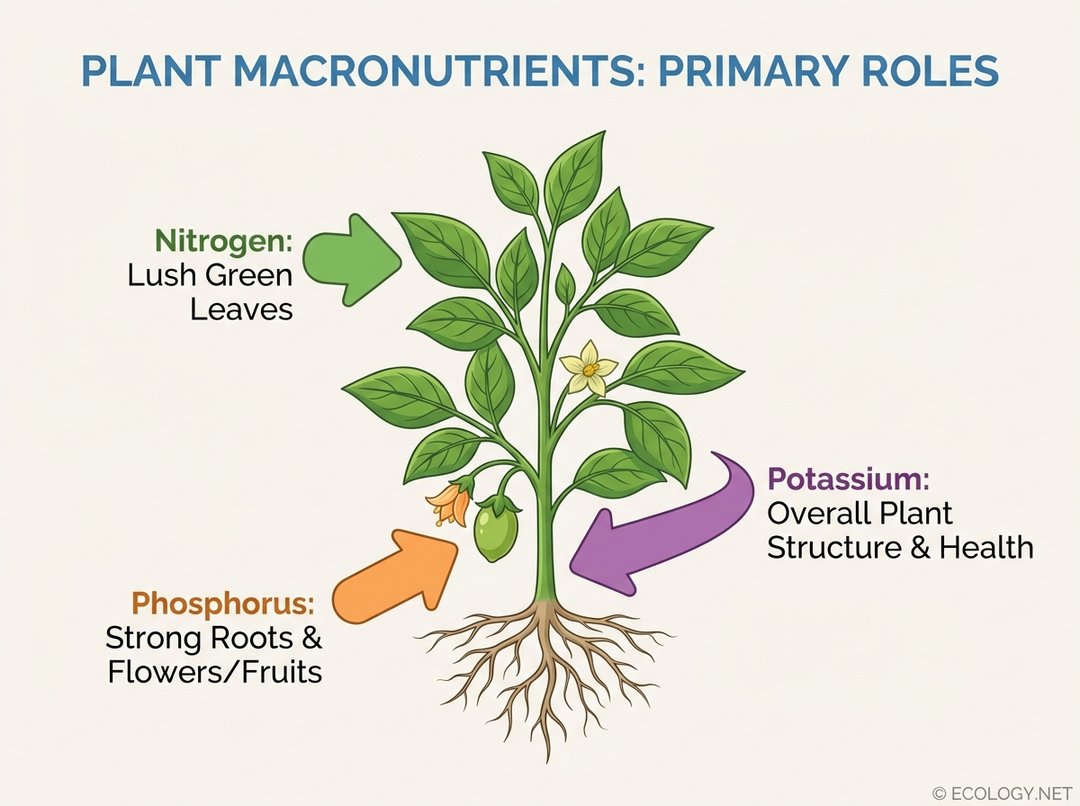

The most critical of these elements are often referred to as macronutrients, needed in larger quantities. Among them, three stand out as the titans of plant nutrition: Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Potassium (K). These three form the famous NPK ratio found on most fertilizer labels, a testament to their paramount importance.

This image visually explains the crucial functions of the three primary macronutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium) in plant growth, as detailed in the ‘What Are Fertilizers and Why Do Plants Need Them?’ section, making the NPK ratio concept clearer.

- Nitrogen (N): The engine of leafy growth. Nitrogen is a fundamental component of chlorophyll, the pigment responsible for photosynthesis, and is crucial for the development of lush, green foliage. A plant deficient in nitrogen will often appear stunted and yellowed.

- Phosphorus (P): The root and bloom booster. Phosphorus plays a vital role in energy transfer within the plant, promoting strong root development, flowering, fruiting, and seed production. It is particularly important during early growth stages and for reproductive processes.

- Potassium (K): The overall health guardian. Potassium contributes to the general vigor and resilience of plants. It helps regulate water uptake and loss, strengthens stems, improves disease resistance, and enhances the quality of fruits and vegetables.

The ABCs of Plant Nutrition: Macronutrients and Micronutrients

While NPK are the stars, a complete understanding of plant nutrition extends beyond these three. Plants require a total of 17 essential nutrients, broadly categorized into macronutrients and micronutrients.

Macronutrients: The Big Eaters

Beyond NPK, plants also need secondary macronutrients in significant amounts:

- Calcium (Ca): Essential for cell wall formation and overall structural integrity, often preventing blossom end rot in tomatoes.

- Magnesium (Mg): A central component of chlorophyll, vital for photosynthesis. Deficiencies often manifest as yellowing between leaf veins.

- Sulfur (S): Important for protein synthesis and enzyme activity, contributing to plant metabolism and vigor.

Micronutrients: Small but Mighty

These elements are needed in much smaller quantities, but their absence can be just as detrimental to plant health as a lack of macronutrients. They often act as co-factors for enzymes, facilitating crucial biochemical reactions.

- Iron (Fe)

- Manganese (Mn)

- Boron (B)

- Zinc (Zn)

- Copper (Cu)

- Molybdenum (Mo)

- Chlorine (Cl)

- Nickel (Ni)

Each of these plays a specific, indispensable role, from aiding in nitrogen fixation to supporting photosynthesis and respiration.

Types of Fertilizers: A World of Options

Fertilizers come in a vast array of forms and compositions, broadly categorized into two main types: organic and inorganic (synthetic).

This image provides a clear visual distinction between organic and inorganic (synthetic) fertilizers, illustrating their different forms and sources as discussed in the ‘Types of Fertilizers: A World of Options’ section.

Organic Fertilizers: Nature’s Bounty

Organic fertilizers are derived from natural sources, primarily plant and animal matter. They include materials like compost, manure, bone meal, blood meal, fish emulsion, and cover crops. Their appeal lies in their holistic approach to soil health.

- Pros:

- Improve soil structure, aeration, and water retention.

- Feed beneficial soil microorganisms, enhancing soil biodiversity.

- Release nutrients slowly over time, reducing the risk of nutrient leaching.

- Less likely to cause nutrient burn to plants.

- Often considered more environmentally friendly when sourced sustainably.

- Cons:

- Nutrient content can be variable and less precise.

- Slower acting, as nutrients must be broken down by soil microbes before becoming available to plants.

- Can be bulky and sometimes have an odor.

Inorganic (Synthetic) Fertilizers: Precision and Potency

Inorganic fertilizers are manufactured through chemical processes, often using mined minerals or atmospheric nitrogen. They are typically highly concentrated and provide nutrients in a readily available form.

- Pros:

- Precise nutrient ratios can be tailored to specific plant needs.

- Fast-acting, delivering nutrients quickly to plants.

- Easy to apply and store, often less bulky than organic options.

- Generally more cost-effective per unit of nutrient.

- Cons:

- Can lead to nutrient runoff and environmental pollution if overused.

- May not contribute to long-term soil health or microbial activity.

- Risk of “nutrient burn” if applied incorrectly or in excessive amounts.

- Manufacturing can be energy-intensive.

Beyond these two main categories, fertilizers also come in various physical forms:

- Granular Fertilizers: Solid pellets or granules, often slow-release, applied by broadcasting or side-dressing.

- Liquid Fertilizers: Concentrated solutions that are diluted with water and applied directly to the soil or as a foliar spray, offering immediate nutrient uptake.

- Slow-Release Fertilizers: Designed to release nutrients gradually over an extended period, minimizing the need for frequent applications and reducing nutrient loss.

How Fertilizers Work: A Journey to the Roots

Regardless of their type, fertilizers ultimately aim to deliver nutrients to plant roots. Plants absorb most of their nutrients in dissolved ionic forms from the soil water. When fertilizers are applied, whether organic matter slowly decomposes or synthetic granules dissolve, they release these essential ions into the soil solution. The roots, through processes like osmosis and active transport, then take up these dissolved nutrients.

The health of the soil plays a crucial role in this process. A vibrant soil ecosystem, rich in organic matter and microbial life, acts as a living pantry, holding onto nutrients and making them available to plants as needed. Organic fertilizers directly enhance this soil health, while inorganic fertilizers provide a direct nutrient boost that can be optimized with good soil management practices.

The Ecological Footprint: Understanding Environmental Impacts

While fertilizers are indispensable for modern agriculture and gardening, their misuse can have significant environmental consequences. The very elements that nourish plants can become pollutants when they escape agricultural systems.

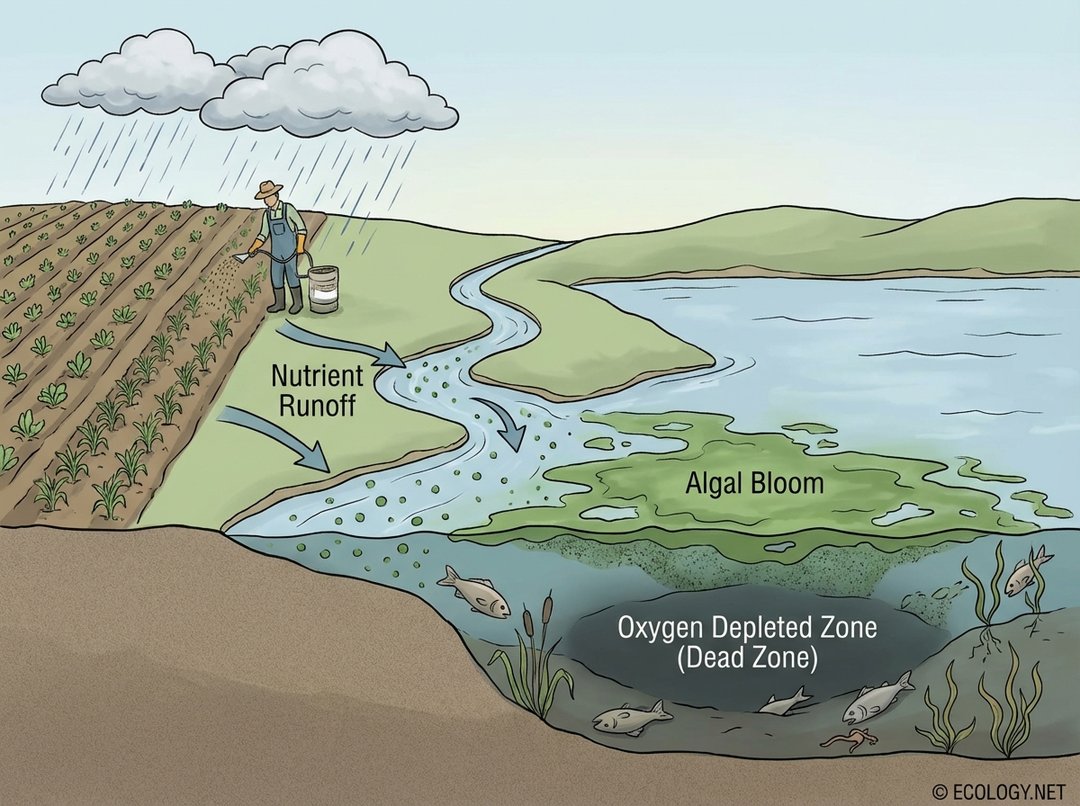

Nutrient Runoff and Eutrophication

One of the most pressing concerns is nutrient runoff. When excess fertilizers are applied, or when heavy rains occur shortly after application, nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus can be washed from fields into nearby waterways. This influx of nutrients acts as a super-fertilizer for aquatic ecosystems, leading to a phenomenon known as eutrophication.

This image visually demonstrates the negative ecological consequences of excess fertilizer, specifically nutrient runoff leading to eutrophication and dead zones, as explained in the ‘Nutrient Runoff and Eutrophication’ subsection.

Eutrophication typically begins with an explosive growth of algae and aquatic plants, often referred to as an “algal bloom.” While initially seeming beneficial, these blooms block sunlight from reaching submerged vegetation, which then dies. As the vast quantities of algae eventually die and decompose, bacteria consume massive amounts of oxygen in the water. This oxygen depletion creates “dead zones” where fish and other aquatic life cannot survive, devastating aquatic biodiversity and ecosystem health. Famous examples include the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, largely fed by nutrient runoff from the Mississippi River basin.

Other Environmental Concerns

- Soil Degradation: Over-reliance on synthetic fertilizers without adequate organic matter can degrade soil structure over time, reducing its ability to retain water and nutrients.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: The production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers is an energy-intensive process, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, nitrogen fertilizers can release nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere.

- Groundwater Contamination: Nitrates, a form of nitrogen, are highly soluble and can leach through the soil profile into groundwater, posing health risks if consumed in drinking water.

Sustainable Fertilization Practices: Cultivating a Greener Future

The challenges posed by fertilizer use are not insurmountable. By adopting sustainable practices, it is possible to harness the benefits of fertilizers while minimizing their environmental footprint. The key lies in informed and responsible application.

- Soil Testing: Regular soil testing is perhaps the most crucial step. It provides a precise understanding of existing nutrient levels and soil pH, allowing for targeted fertilizer application and avoiding unnecessary additions.

- Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, Right Place (4R Nutrient Stewardship): This principle guides efficient fertilizer use:

- Right Source: Choosing the appropriate fertilizer type (organic, synthetic, slow-release) for the crop and soil conditions.

- Right Rate: Applying only the amount of nutrients needed by the crop, based on soil tests and yield goals.

- Right Time: Applying fertilizers when plants can best utilize them, often coinciding with specific growth stages, to minimize losses.

- Right Place: Placing fertilizers where roots can access them efficiently, such as banding near the root zone, rather than broadcasting widely.

- Cover Cropping and Crop Rotation: These agricultural practices enhance soil health, add organic matter, and can naturally fix nitrogen, reducing the need for synthetic inputs.

- Precision Agriculture: Utilizing technologies like GPS, sensors, and variable-rate applicators allows farmers to apply fertilizers precisely where and when they are needed, optimizing nutrient use efficiency.

- Composting and Manure Management: Properly composting organic waste and managing animal manures not only diverts waste from landfills but also creates nutrient-rich soil amendments.

Conclusion

Fertilizers are a cornerstone of modern food production and a vital tool for maintaining healthy landscapes. They empower plants to reach their full potential, ensuring food security and supporting diverse ecosystems. However, their power comes with a profound responsibility. By understanding the intricate science behind plant nutrition, recognizing the environmental risks of misuse, and embracing sustainable practices, humanity can continue to leverage the benefits of fertilizers while safeguarding the health of our planet for generations to come. The future of our fields and waterways depends on our collective commitment to intelligent and ecological stewardship.