Life, in all its magnificent forms, from the smallest bacterium to the largest whale, shares a fundamental secret: the ability to harness energy. This energy, the very fuel that powers every blink, every thought, every beat of a heart, is meticulously extracted from food through a remarkable process known as cellular respiration. It is the universal engine of life, tirelessly working within every cell to keep organisms alive and thriving.

Imagine your body as a high-performance vehicle. Just as a car needs fuel to run, your cells need a constant supply of energy to perform their myriad functions. Cellular respiration is the intricate biochemical pathway that converts the chemical energy stored in nutrients, primarily glucose, into a usable form of energy called adenosine triphosphate, or ATP. Without this vital process, life as we know it simply would not exist.

The Energy Currency of Life: ATP

Before delving into the mechanics of cellular respiration, it is essential to understand its ultimate product: ATP. Think of ATP as the universal energy currency of the cell. Just as you use money to buy goods and services, cells use ATP to power nearly all their activities. Whether it is muscle contraction, nerve impulse transmission, protein synthesis, or active transport, ATP is the direct source of energy.

ATP is a relatively small molecule, but its structure holds immense power. It consists of an adenine base, a ribose sugar, and three phosphate groups. The magic happens in the bonds between these phosphate groups, particularly the terminal one. When a cell needs energy, it breaks this bond, releasing a significant amount of energy and converting ATP into ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and an inorganic phosphate. This released energy is then immediately put to work. The cell constantly recycles ADP back into ATP, creating a continuous energy cycle.

Aerobic Respiration: The Oxygen Advantage

The most efficient and prevalent form of cellular respiration is aerobic respiration, which requires oxygen. This process is like a finely tuned power plant, extracting the maximum amount of energy from glucose. It unfolds in three main stages:

1. Glycolysis: The Initial Split

Glycolysis, meaning “sugar splitting,” is the first step in both aerobic and anaerobic respiration. It occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell and does not require oxygen. During glycolysis, a single molecule of glucose, a six-carbon sugar, is broken down into two molecules of pyruvate, a three-carbon compound. This initial breakdown yields a small net gain of two ATP molecules and two molecules of NADH, an electron carrier.

2. The Krebs Cycle (Citric Acid Cycle): The Central Hub

If oxygen is present, the pyruvate molecules produced during glycolysis move into the mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses. Here, each pyruvate is converted into acetyl-CoA, which then enters the Krebs cycle, also known as the citric acid cycle. This cycle is a series of eight enzymatic reactions that completely oxidize the acetyl-CoA. For each turn of the cycle, carbon dioxide is released, and more electron carriers, NADH and FADH2, are generated, along with a small amount of ATP.

3. Electron Transport Chain and Oxidative Phosphorylation: The Grand Finale

The electron transport chain is where the vast majority of ATP is produced. It is a series of protein complexes embedded in the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. The NADH and FADH2 molecules, carrying high-energy electrons from glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, deliver these electrons to the chain. As electrons pass from one complex to the next, they release energy, which is used to pump protons (hydrogen ions) from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space, creating a proton gradient.

This gradient represents stored potential energy. Protons then flow back into the matrix through a special enzyme called ATP synthase, much like water turning a turbine in a hydroelectric dam. This flow drives the synthesis of large quantities of ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate, a process called oxidative phosphorylation. Oxygen acts as the final electron acceptor at the end of the chain, combining with electrons and protons to form water. This crucial role of oxygen prevents a bottleneck in the electron transport chain, allowing the continuous production of ATP.

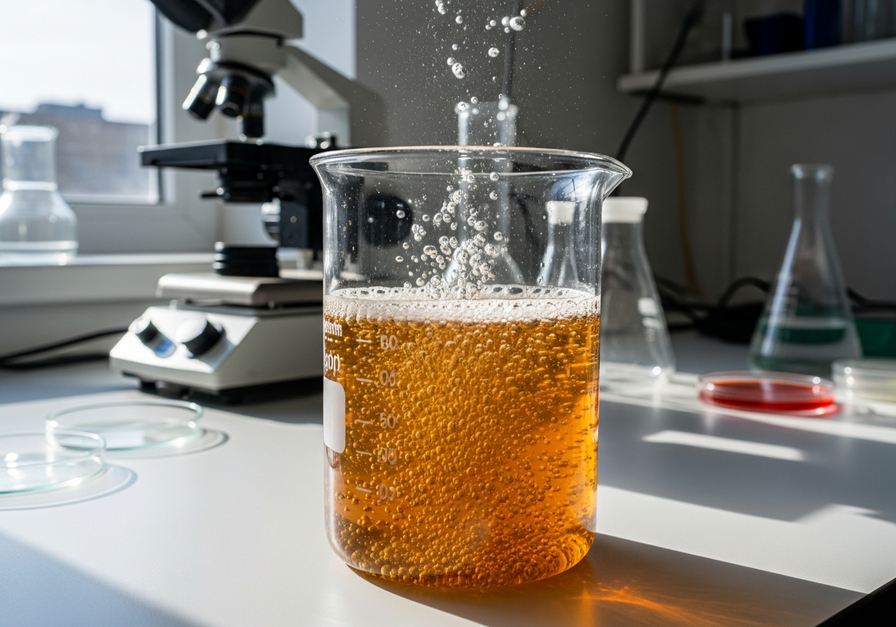

This image brings the reader face-to-face with the cell’s ATP-producing machinery, visualizing the site of oxidative phosphorylation described in the article.

Anaerobic Respiration: Life Without Oxygen

While aerobic respiration is highly efficient, life sometimes finds itself in environments where oxygen is scarce or absent. In such situations, cells resort to anaerobic respiration, a less efficient but vital pathway to generate ATP. This process also begins with glycolysis, producing pyruvate and a small amount of ATP. However, instead of entering the Krebs cycle, pyruvate undergoes fermentation.

Fermentation: Two Common Paths

There are two primary types of fermentation:

- Lactic Acid Fermentation: In this process, pyruvate is converted into lactic acid. This occurs in human muscle cells during intense exercise when oxygen supply cannot keep up with energy demand. The buildup of lactic acid contributes to muscle fatigue and soreness. Certain bacteria also perform lactic acid fermentation, which is crucial in producing yogurt, cheese, and sauerkraut.

- Alcoholic Fermentation: Yeast and some bacteria convert pyruvate into ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide. This process is fundamental to baking, where the carbon dioxide causes bread to rise, and to brewing, where ethanol is the desired product in beer and wine.

The image illustrates anaerobic respiration and fermentation, providing a tangible visual of how cells generate ATP without oxygen, as discussed in the article.

It is important to note that fermentation does not produce any additional ATP beyond the two molecules generated during glycolysis. Its primary purpose is to regenerate NAD+, an electron carrier essential for glycolysis to continue, thereby allowing a continuous, albeit limited, supply of ATP in the absence of oxygen.

Cellular Respiration in Action: Everyday Examples

The principles of cellular respiration are not confined to textbooks; they are at play all around us and within us every second.

- Human Performance: When an athlete sprints, their muscles initially rely on aerobic respiration. However, as the intensity increases, oxygen delivery may become insufficient, and muscles switch to lactic acid fermentation to meet the immediate energy demand. This is why sprinters can only maintain top speed for short bursts.

- Plant Life: Plants, like animals, perform cellular respiration to power their growth, reproduction, and maintenance. While they produce glucose through photosynthesis, they must then break it down via respiration to access its energy. Respiration occurs in plant cells continuously, day and night.

- Microbial Worlds: From the bacteria in our gut aiding digestion to the decomposers in soil breaking down organic matter, microorganisms utilize diverse forms of cellular respiration. Some thrive in oxygen-rich environments, while others are obligate anaerobes, perishing in the presence of oxygen.

This photo showcases the real-world demand for ATP during muscle contraction, linking the cellular processes described in the article to everyday physical activity.

The Ecological Perspective: A Global Energy Cycle

From an ecological standpoint, cellular respiration is not just an individual cellular process; it is a critical component of global biogeochemical cycles, particularly the carbon cycle. Photosynthesis, performed by plants and other producers, captures atmospheric carbon dioxide and converts it into organic compounds, essentially storing solar energy. Cellular respiration, performed by nearly all living organisms, then releases this stored energy by breaking down those organic compounds, returning carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

This continuous dance between photosynthesis and respiration maintains the balance of gases in our atmosphere and drives the flow of energy through ecosystems. Producers create the fuel, and consumers and decomposers burn it, ensuring that energy is constantly recycled and transformed, sustaining the intricate web of life on Earth.

Beyond the Basics: Regulation and Efficiency

Cellular respiration is a highly regulated process. Cells do not simply burn glucose indiscriminately. Various feedback mechanisms ensure that ATP is produced only when needed and at appropriate rates. For example, high levels of ATP can inhibit certain enzymes in glycolysis and the Krebs cycle, slowing down respiration. Conversely, high levels of ADP or low levels of ATP can stimulate these pathways, increasing energy production.

The efficiency of aerobic respiration is remarkable. From a single molecule of glucose, approximately 30-32 molecules of ATP can be generated. While this might seem like a lot, it represents about 34% of the total energy stored in glucose, with the remaining energy lost as heat. This heat is not entirely wasted; it helps maintain body temperature in warm-blooded animals. Anaerobic respiration, in contrast, is far less efficient, yielding only 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule.

The Unseen Powerhouse of Life

Cellular respiration is an extraordinary testament to the elegance and efficiency of biological systems. It is the fundamental process that underpins all life, transforming the chemical energy in our food into the usable energy that powers every single function of our bodies and every interaction within ecosystems. Understanding cellular respiration provides a profound appreciation for the intricate machinery within each cell and the grand energy cycles that sustain our planet. It is the unseen powerhouse, tirelessly working, allowing life to flourish in all its diverse and dynamic forms.