Life as we know it hinges on a fundamental element: oxygen. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, and of course, every human being, oxygen fuels the intricate machinery of existence. But what happens when this vital gas becomes scarce? This is the realm of hypoxia, a condition where tissues and cells are deprived of adequate oxygen supply. It is a concept that spans medical emergencies, high-altitude adventures, and even vast oceanic ecosystems, presenting a fascinating and often critical challenge to life.

Understanding Hypoxia: The Breath of Life Deprived

At its core, hypoxia means “low oxygen.” It is not merely about a lack of oxygen in the air we breathe, but rather a deficiency at the cellular level, where oxygen is ultimately utilized to generate energy. Our bodies are incredibly sensitive to oxygen levels. Even a slight drop can trigger a cascade of physiological responses, from increased heart rate and rapid breathing to more severe neurological and organ damage if prolonged.

Think of oxygen as the essential fuel for a car engine. Without enough fuel, the engine sputters, loses power, and eventually stops. Similarly, without sufficient oxygen, our cells cannot perform their metabolic functions, leading to cellular distress and, in severe cases, cell death. This fundamental need for oxygen makes hypoxia a critical area of study across biology, medicine, and environmental science.

The Many Faces of Oxygen Deprivation

Hypoxia is not a single, monolithic condition. Instead, it manifests in several distinct forms, each with its own causes and implications. Understanding these different types is key to grasping the full scope of this vital concept.

- Hypoxic Hypoxia (Altitude Hypoxia): This is perhaps the most commonly understood form, occurring when the partial pressure of oxygen in the inhaled air is reduced.

Imagine standing atop a towering mountain peak. The air is thin, crisp, and exhilarating, but it also contains significantly less oxygen than at sea level. This reduction in atmospheric oxygen pressure means that less oxygen enters your lungs and subsequently your bloodstream. This is precisely why mountaineers often rely on supplemental oxygen at extreme altitudes.

The human body is remarkably adaptable, and given time, it can acclimatize to moderate altitudes by producing more red blood cells. However, beyond a certain elevation, the oxygen deficit becomes too great for natural adaptation, necessitating external oxygen sources to prevent acute mountain sickness or more severe conditions like high-altitude cerebral or pulmonary edema.

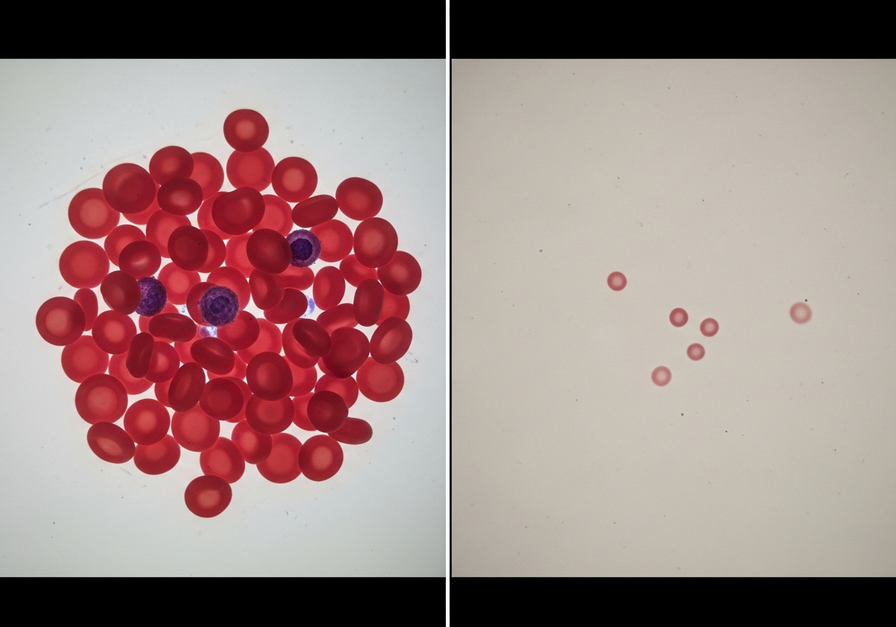

- Anemic Hypoxia: In this type, the problem isn’t with the amount of oxygen available, but with the blood’s ability to transport it.

Our blood’s primary oxygen carrier is hemoglobin, a protein found within red blood cells. Anemic hypoxia occurs when there is an insufficient number of healthy red blood cells or a reduced amount of functional hemoglobin. This can be due to various forms of anemia, blood loss, or even carbon monoxide poisoning, where carbon monoxide binds to hemoglobin far more readily than oxygen, effectively “hijacking” the transport system.

Without enough healthy hemoglobin to pick up oxygen from the lungs and deliver it to the tissues, the body’s cells starve for oxygen, even if the air itself is rich in it. This visual comparison highlights the stark difference in oxygen-carrying potential between healthy and anemic blood.

- Stagnant (Ischemic) Hypoxia: Here, the issue lies with blood flow. Even if the blood is well-oxygenated, if it cannot reach the tissues efficiently, those tissues will suffer from oxygen deprivation.

Imagine a traffic jam on a highway. Even if there are plenty of cars (oxygenated blood) at the start, if the flow is blocked, no cars can reach their destination. This is analogous to stagnant hypoxia, which can be caused by conditions like heart failure, shock, or localized blockages such as blood clots in arteries. A stroke, for instance, is a form of localized stagnant hypoxia in the brain, where a blocked artery prevents oxygenated blood from reaching a specific brain region.

- Histotoxic Hypoxia: This is a more insidious form where cells receive oxygen, but are unable to utilize it.

In this scenario, the “fuel” (oxygen) reaches the “engine” (cell), but the engine’s internal mechanisms are poisoned and cannot process the fuel. Cyanide poisoning is a classic example of histotoxic hypoxia. Cyanide interferes with the enzymes responsible for cellular respiration, the process by which cells use oxygen to produce energy. Even with abundant oxygen in the blood, the cells cannot access its life-giving power.

Hypoxia in the Environment: A Silent Crisis

While often discussed in a medical context, hypoxia is also a critical ecological phenomenon, particularly in aquatic environments. These “dead zones” are a stark reminder of humanity’s impact on natural systems.

Oceanic hypoxia occurs when the concentration of dissolved oxygen in water drops to levels too low to sustain most marine life. These areas, often referred to as “dead zones,” are expanding globally, posing a significant threat to biodiversity and fisheries. The image above vividly portrays the devastating effects of such an environment.

The Making of a Dead Zone

The primary driver of marine dead zones is nutrient pollution, largely from agricultural runoff and wastewater. Here is how it unfolds:

- Nutrient Overload: Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers, sewage, and industrial waste flow into rivers and eventually into coastal waters.

- Algal Blooms: These nutrients act as a super-fertilizer for microscopic algae, leading to rapid, explosive growth known as an algal bloom.

- Decomposition and Oxygen Depletion: When these vast quantities of algae eventually die, they sink to the bottom. Bacteria then decompose this organic matter, a process that consumes large amounts of dissolved oxygen from the water.

- Stratification: In many coastal areas, layers of water with different temperatures or salinities prevent mixing, trapping the oxygen-depleted water at the bottom.

- Ecological Collapse: Fish and other mobile marine organisms flee the hypoxic areas, while sessile creatures like crabs, clams, and corals, unable to escape, suffocate and die. This creates an ecological void, a “dead zone.”

Notable examples include the vast dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, fed by the Mississippi River, and similar areas in the Baltic Sea and off the coast of Oregon. Climate change exacerbates this problem by warming ocean waters, which hold less dissolved oxygen, and by altering ocean currents, further contributing to stratification.

The Intricate Dance of Oxygen: A Deeper Dive

To truly appreciate the impact of hypoxia, it is helpful to understand the sophisticated mechanisms our bodies and ecosystems employ to manage oxygen.

Oxygen Transport and Cellular Respiration

In humans and many animals, oxygen enters the lungs, where it diffuses across thin membranes into the bloodstream. Here, it binds to hemoglobin in red blood cells, forming oxyhemoglobin. This oxygen-rich blood is then pumped by the heart to every tissue and cell in the body. At the cellular level, oxygen detaches from hemoglobin and diffuses into the cells, specifically into the mitochondria.

Mitochondria are often called the “powerhouses” of the cell because they perform cellular respiration, a complex biochemical process that uses oxygen to break down glucose and produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency of the cell. Without oxygen, this highly efficient aerobic respiration cannot occur, forcing cells to rely on less efficient anaerobic pathways, which produce far less ATP and generate harmful byproducts like lactic acid.

Environmental Oxygen Dynamics

In aquatic environments, oxygen dissolves directly from the atmosphere into the water, and is also produced by photosynthetic organisms like phytoplankton and aquatic plants. Factors influencing dissolved oxygen levels include:

- Temperature: Colder water holds more dissolved oxygen than warmer water.

- Salinity: Freshwater holds more dissolved oxygen than saltwater.

- Atmospheric Pressure: Higher atmospheric pressure leads to more dissolved oxygen.

- Turbulence: Waves and currents increase the surface area for gas exchange, enhancing oxygen dissolution.

- Biological Activity: Photosynthesis adds oxygen, while respiration by aquatic organisms and decomposition by bacteria consume it.

When the rate of oxygen consumption exceeds the rate of oxygen replenishment, hypoxia sets in, leading to the devastating consequences observed in dead zones.

Detecting and Mitigating Hypoxia

Addressing hypoxia requires both medical intervention and environmental stewardship.

Medical Approaches

In clinical settings, hypoxia is detected through various methods:

- Pulse Oximetry: A non-invasive device placed on a finger measures the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin in arterial blood.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) Test: A more invasive test that directly measures the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and carbon dioxide in arterial blood, along with pH and bicarbonate levels.

- Clinical Signs: Symptoms like shortness of breath, confusion, cyanosis (bluish discoloration of skin), and rapid heart rate can indicate hypoxia.

Treatment often involves administering supplemental oxygen, addressing the underlying cause (e.g., blood transfusion for anemia, improving blood flow for stagnant hypoxia), or using medications to support respiratory function.

Environmental Solutions

Mitigating environmental hypoxia, particularly in marine dead zones, focuses on reducing nutrient pollution:

- Agricultural Best Practices: Implementing precision farming techniques, optimizing fertilizer use, creating riparian buffers, and managing livestock waste.

- Wastewater Treatment: Upgrading municipal wastewater treatment plants to remove nitrogen and phosphorus more effectively.

- Stormwater Management: Reducing runoff from urban areas through green infrastructure and permeable surfaces.

- Restoration Efforts: Restoring wetlands and coastal habitats that can filter pollutants before they reach larger bodies of water.

- Policy and Regulation: Implementing stricter regulations on industrial discharges and agricultural practices.

Conclusion

Hypoxia, in all its forms, serves as a powerful reminder of the delicate balance required for life to thrive. Whether it is a climber gasping for air on a mountain peak, a patient struggling with anemia, or an entire marine ecosystem suffocating in a dead zone, the absence of sufficient oxygen underscores its fundamental importance. By understanding the causes and mechanisms of hypoxia, we can better protect human health and work towards a more sustainable future for our planet’s vital aquatic environments, ensuring that the breath of life continues to flow freely for all.