In the vast theater of the natural world, survival often hinges on a delicate balance of adaptation and deception. Among the most fascinating strategies employed by countless species is mimicry, an evolutionary marvel where one organism evolves to resemble another, or even its surroundings, to gain a crucial advantage. This intricate dance of appearance and perception is not merely a trick of the eye but a profound testament to the power of natural selection, shaping life in countless unexpected ways.

What is Mimicry? The Art of Deception

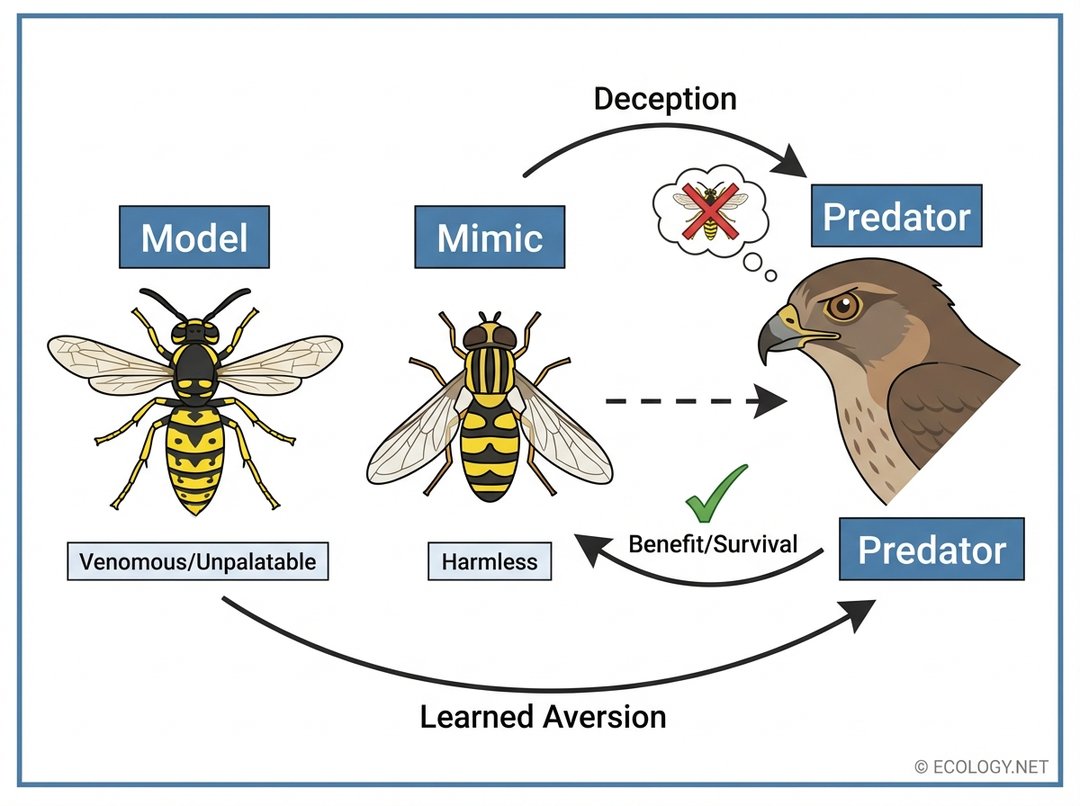

At its core, mimicry is a biological phenomenon where a species, known as the “mimic,” evolves to share characteristics with another species, the “model,” to deceive a third party, often a “receiver” or “dupe.” This deception typically confers a survival or reproductive advantage to the mimic. The characteristics shared can be visual, auditory, olfactory, or even tactile, creating a sophisticated illusion that fools predators, prey, or even potential mates.

Imagine a scenario where a dangerous animal, perhaps a venomous snake, is easily recognized by its distinctive markings. Over time, a harmless snake species might evolve similar markings. Predators that have learned to avoid the venomous model will then also avoid the harmless mimic, mistaking it for the dangerous one. This simple yet powerful mechanism underpins the diverse world of mimicry.

Why Mimic? The Evolutionary Advantage

The driving force behind mimicry is survival and reproduction. By mimicking another organism, a species can:

- Deter Predators: This is perhaps the most common form, where a harmless or palatable species mimics a dangerous, toxic, or unpalatable one.

- Attract Prey: Some predators use mimicry to lure unsuspecting prey closer, making capture easier.

- Facilitate Reproduction: Mimicry can play a role in pollination or mating, where one species mimics another to ensure its reproductive success.

- Gain Access to Resources: In some cases, mimics can gain entry to protected areas or exploit resources by appearing to be a different species.

Each instance of mimicry is a finely tuned evolutionary adaptation, honed over generations through the relentless pressure of natural selection.

Types of Mimicry: A Spectrum of Deception

Mimicry is not a monolithic concept but encompasses several distinct types, each with its own unique evolutionary pathway and ecological implications.

Defensive Mimicry: Protection Through Impersonation

Defensive mimicry is perhaps the most widely recognized form, where an organism mimics another to avoid being eaten or harmed.

Batesian Mimicry: The Harmless Impostor

Named after the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, Batesian mimicry occurs when a palatable, defenseless species (the mimic) evolves to imitate an unpalatable or dangerous species (the model). The mimic benefits because predators, having learned to avoid the model, will also avoid the mimic. For this to work effectively, the model must be more abundant than the mimic, ensuring predators encounter the real threat often enough to learn the association.

A classic example of Batesian mimicry involves the Viceroy butterfly (Limenitis archippus) and the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus). Monarchs feed on milkweed as caterpillars, accumulating toxins that make them unpalatable to birds. Viceroys, while not toxic, have evolved to closely resemble Monarchs in their orange and black wing patterns. Birds that have had a bad experience with a Monarch will typically avoid a Viceroy, mistaking it for its toxic counterpart.

Other examples include hoverflies mimicking wasps and bees, or non-venomous snakes mimicking venomous coral snakes.

Müllerian Mimicry: Strength in Numbers

Coined by German naturalist Fritz Müller, Müllerian mimicry involves two or more unpalatable or dangerous species that evolve to resemble each other. Unlike Batesian mimicry, where only the mimic benefits, in Müllerian mimicry, all species involved benefit. Predators learn to avoid the shared warning signal more quickly, as encounters with any of the mimicking species reinforce the negative association. This effectively dilutes the cost of educating predators across multiple species.

- Example: Many species of bees and wasps, all capable of stinging, share similar black and yellow striped patterns. A bird that stings itself on a yellow jacket will subsequently avoid all insects with similar markings, benefiting not only yellow jackets but also bumblebees and other wasps that share the pattern.

- Example: Heliconius butterflies in the Neotropics, many of which are toxic, exhibit striking similarities in their wing patterns across different species, reinforcing their unpalatability to predators.

Wasmannian Mimicry: Infiltrating the Colony

This specialized form of mimicry involves mimics that live within the nests or colonies of social insects, such as ants or termites. The mimic resembles its host species to avoid detection and gain access to the colony’s resources, often at the host’s expense.

- Example: Many species of rove beetles (family Staphylinidae) have evolved to mimic the chemical and tactile cues of ants, allowing them to live undetected within ant nests, where they may feed on ant larvae or stored food.

Aggressive Mimicry: The Hunter’s Disguise

Not all mimicry is for defense. Aggressive mimicry involves a predator or parasite mimicking a harmless species or an attractive resource to deceive its prey or host. This allows the mimic to approach its target without being detected as a threat.

The deep-sea Anglerfish is a prime example of aggressive mimicry. It possesses a bioluminescent lure, a modified dorsal fin ray, that dangles in front of its mouth. This lure often resembles a small, harmless fish or worm. Unsuspecting smaller fish, attracted to what they perceive as an easy meal, swim directly into the Anglerfish’s cavernous jaws.

- Example: Some species of fireflies (genus Photuris) mimic the flash patterns of other firefly species (genus Photinus) to lure males of those species, only to devour them.

- Example: Certain orchids mimic the appearance and scent of female insects to attract male pollinators, which then inadvertently transfer pollen.

Reproductive Mimicry: The Art of Seduction

Reproductive mimicry focuses on deceiving other organisms for the purpose of reproduction, often involving pollination or mating strategies.

- Example: Many orchids employ floral mimicry, where their flowers resemble female insects, attracting male insects that attempt to mate with the flower, thereby facilitating pollination. This is a form of aggressive mimicry from the plant’s perspective, but it is specifically for reproduction.

- Example: Cuckoo birds are famous for their brood parasitism, laying their eggs in the nests of other bird species. The cuckoo eggs often mimic the appearance of the host’s eggs, deceiving the host parents into incubating and raising the cuckoo chick as their own.

Automimicry: Mimicking Oneself

Automimicry occurs when parts of an animal’s body mimic other parts of its own body. This often serves to confuse predators or direct attacks away from vital organs.

- Example: Many butterflies and fish have “eyespots” on their wings or tails. These spots often resemble the eyes of a larger animal, potentially startling a predator or causing it to strike at a less vulnerable part of the body, allowing the mimic to escape with only minor damage.

- Example: Some snakes have tails that resemble their heads, and when threatened, they might raise their tail and move it in a head-like fashion, drawing attention away from their actual head.

The Intricacies of Mimicry: Beyond Visuals

While visual mimicry is the most apparent, the world of deception extends far beyond what meets the eye. Mimicry can engage multiple senses, creating even more sophisticated illusions.

- Auditory Mimicry: Some animals mimic the sounds of dangerous species. For instance, certain non-venomous snakes can mimic the rattling sound of rattlesnakes to deter predators.

- Olfactory Mimicry: Chemical mimicry is common, especially among insects. Wasmannian mimics, for example, often produce chemicals that mimic the pheromones of their host ants, allowing them to blend in chemically. Some plants also mimic the scent of decaying flesh to attract carrion-feeding insects for pollination.

- Tactile Mimicry: Mimics can also evolve to feel like their models. Some beetles that live in ant nests have body shapes and textures that mimic ants, further enhancing their disguise.

The combination of these sensory deceptions creates a multi-layered illusion, making it incredibly difficult for receivers to distinguish between the mimic and the model.

Evolutionary Arms Race: The Dynamics of Mimicry

Mimicry is not a static phenomenon but rather an ongoing evolutionary arms race. As mimics become better at their deception, receivers (predators, prey, or hosts) evolve better detection abilities. This, in turn, drives mimics to refine their impersonations even further, leading to a continuous cycle of adaptation and counter-adaptation.

For Batesian mimicry, if mimics become too numerous, predators might learn that the warning signal is not always reliable, leading to a breakdown of the mimicry system. This pressure keeps the mimic population in check relative to the model. In Müllerian mimicry, the shared signal becomes stronger as more species adopt it, reinforcing its effectiveness.

The study of mimicry offers profound insights into the mechanisms of evolution, demonstrating how species interact and adapt in complex ecological webs. It highlights the incredible diversity of life’s strategies for survival and reproduction, reminding us that in nature, appearances can be deceiving, and often, that is precisely the point.

Conclusion

Mimicry stands as one of nature’s most elegant and compelling examples of natural selection at work. From the harmless hoverfly impersonating a stinging wasp to the cunning anglerfish luring its prey with a deceptive light, these evolutionary adaptations underscore the constant struggle for survival and the ingenious ways organisms have found to gain an advantage. Understanding mimicry not only enriches our appreciation for the intricate beauty of the natural world but also provides a window into the dynamic processes that shape biodiversity on our planet.